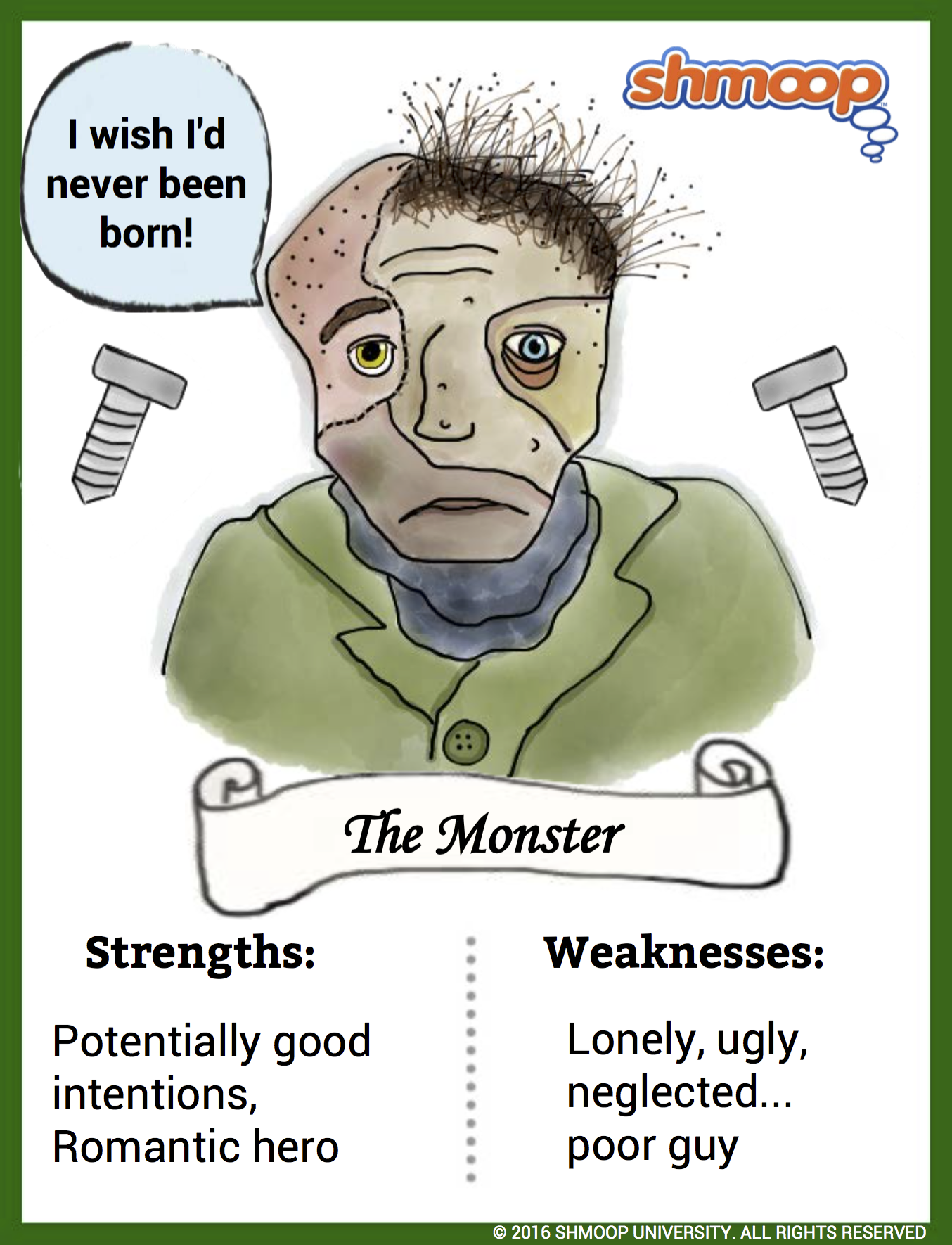

Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Poor monster. He has a face not even a mother/ mad scientist could love… but at least it comes with a heart of gold. Or does it? We'd like to give him the benefit of the doubt—but, when it comes down to it, we'd be pulling out the mace and pressing the panic button on our cellphone if we saw him in a dark alley. So, let's start with the bad.

The Other

And it's really not pretty. Check out how Victor describes him:

His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips. (5.2)

Monstrous? We'll say. And when you take a closer look at this description, the real horror seems to be the contrast: flowing black hair and white teeth juxtaposed with his shriveled face and "straight black lips." We don't exactly blame Victor for running out the door, but we do have to point out that Victor has already revealed himself to put a little too much emphasis on appearance. (Check out his "Character Analysis" for more about that.)

Unfortunately, Victor isn't the only one who's terrified of the monster on sight. The sweet, gentle family he's been spying on in the forest falls to pieces when they see him: Agatha faints, Safie runs away, and Felix beats him with a stick (15.37). Not a good beginning. Even Walton, who knows the whole story, can't deal: "Never did I behold a vision so horrible as his face," he says: "I shut my eyes involuntarily" (24.56).

Okay, so we've established that he's ugly. But we haven't established whether he's actually a monster—or whether he becomes a monster because "where they [i.e., all people everywhere] ought to see a feeling and kind friend, they behold only a detestable monster" (15.26)

Heart of Gold?

When the monster describes himself, it's all sunshine and light. He has visions of "amiable and lovely creatures" keeping him company (15.11); he admires Agatha and Felix as "superior beings" (12.17); he describes himself as having "good dispositions" and tells De Lacey that "my life has been hitherto harmless and in some degree beneficial" (15.25); and he uses "extreme labour" to rescue a young girl from drowning" (16.19). But no matter what he does, his actions are always misinterpreted. Felix and Agatha think he's come to attack their father; the public assumes he's trying to murder the young girl instead of rescuing her; William Frankenstein assumes that he's going to kill him.

The moment he's accused of trying to murder the girl is a real turning point for the monster.

This was then the reward of my benevolence! I had saved a human being from destruction, and as a recompense I now writhed under the miserable pain of a wound which shattered the flesh and bone. The feelings of kindness and gentleness which I had entertained but a few moments before gave place to hellish rage and gnashing of teeth. Inflamed by pain, I vowed eternal hatred and vengeance to all mankind. (16.19-20)

Essentially, Shelley seems to be saying that we (society) get the monsters we deserve. By neglecting and shunning people with socially unacceptable appearances or behaviors, we create mass murderers. (Hm, sounds surprisingly like an anti-bullying PSA.) If we accept the monster's word—that he was born good and made evil—then one of the book's major moral points is that we as a society have a responsibility to reach out to our outcast members.

Superhero

In Victor's "Character Analysis," we suggested that Shelley wrote him based on the Romantic ideas of her husband and his friends: an individual who went beyond society's norms to bring enlightenment back to us poor mortals. And we saw how well that worked out for Victor. But what if we saw the monster as a Romantic figure, too? Check out his description of himself:

I was dependent on none and related to none. The path of my departure was free, and there was none to lament my annihilation. My person was hideous and my stature gigantic. What did this mean? Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination? These questions continually recurred. (15.5)

If you leave out the bit about the "hideous" person, this is a pitch-perfect description of a Romantic hero: a radically independent dude who won't let the man tell him what to do, a kind of superhero who sets out to solve the mysteries of life. (If you want to hear this theory with more $10 words, check out this 1964 article.)

And if you want more proof that Shelley may have intended the monster to be heroic, check out this description of his strength:

I was not even of the same nature as man. I was more agile than they and could subsist upon coarser diet; I bore the extremes of heat and cold with less injury to my frame; my stature far exceeded theirs. (13.17)

Monster? Maybe. But if you closed your eyes, he'd sound a lot like a better version of humanity.

Lone Ranger

But being a superhero isn't all it's cracked up to be. It's lonely at the top, and not just because the monster is "shunned and hated by all mankind" (17.5). He's shunned and hated by all womankind, too: "Shall each man," he says, "find a wife for his bosom, and each beast have his mate, and I be alone?" (20.11). Even our cold hearts are touched by this plea. He begs Frankenstein to make him a mate, and he really seems sincere when he says that he's just planning to move to South America and eat "acorns and berries" (17.9).

(Quick Brain Snack: Percy Shelley advocated vegetarianism—and having the monster say that he does not "destroy the lamb and the kid to glut [his] appetite" (17.9) sounds a lot like he really is a superior form of human, doesn't it?)

Essentially, the monster has no community. Even Satan, he says, had fellow fallen angels—but the monster is totally alone. No wonder he has a death wish.

Adam or Satan?

If you're feeling pretty conflicted about the monster right now, that's because he's supposed to be essentially dualistic. Is he good or evil? Is he a lesser type of man, or a greater type of man? Is he Adam—or is he Satan?

The Adam/ Satan duality is super important, because one of the monster's favorite books is Paradise Lost. In Paradise Lost, Milton suggests that Satan is jealous of Adam for having Eve and a sweet garden to live in. Sounds a lot like the monster, right? Sure. Unless we think of him as a better type of man, and as (along with Mrs. Monster) the founder of a new breed of ugly but heroic creatures. Look at the way he describes his plan for the future:

I will go to the vast wilds of South America. My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment. My companion will be of the same nature as myself and will be content with the same fare. We shall make our bed of dried leaves; the sun will shine on us as on man and will ripen our food. (17.9)

Eating berries, living in the "wilds," sleeping in the leaves, not to mention being "created" rather than born: it sounds a lot like Book 5 of Paradise Lost. So, which is it?

Well, both. The whole point (we think) is that the monster is both. He's both good and bad. He's a little scientist, trying to figure out the secrets of life—and then setting fire to the ants he's been studying with a microscope. (Figuratively, folks.) He loves people, but he hates them. He wants to run away and live in the woods, and he just wants his mommy to love him. In other words, he's a lot like us.