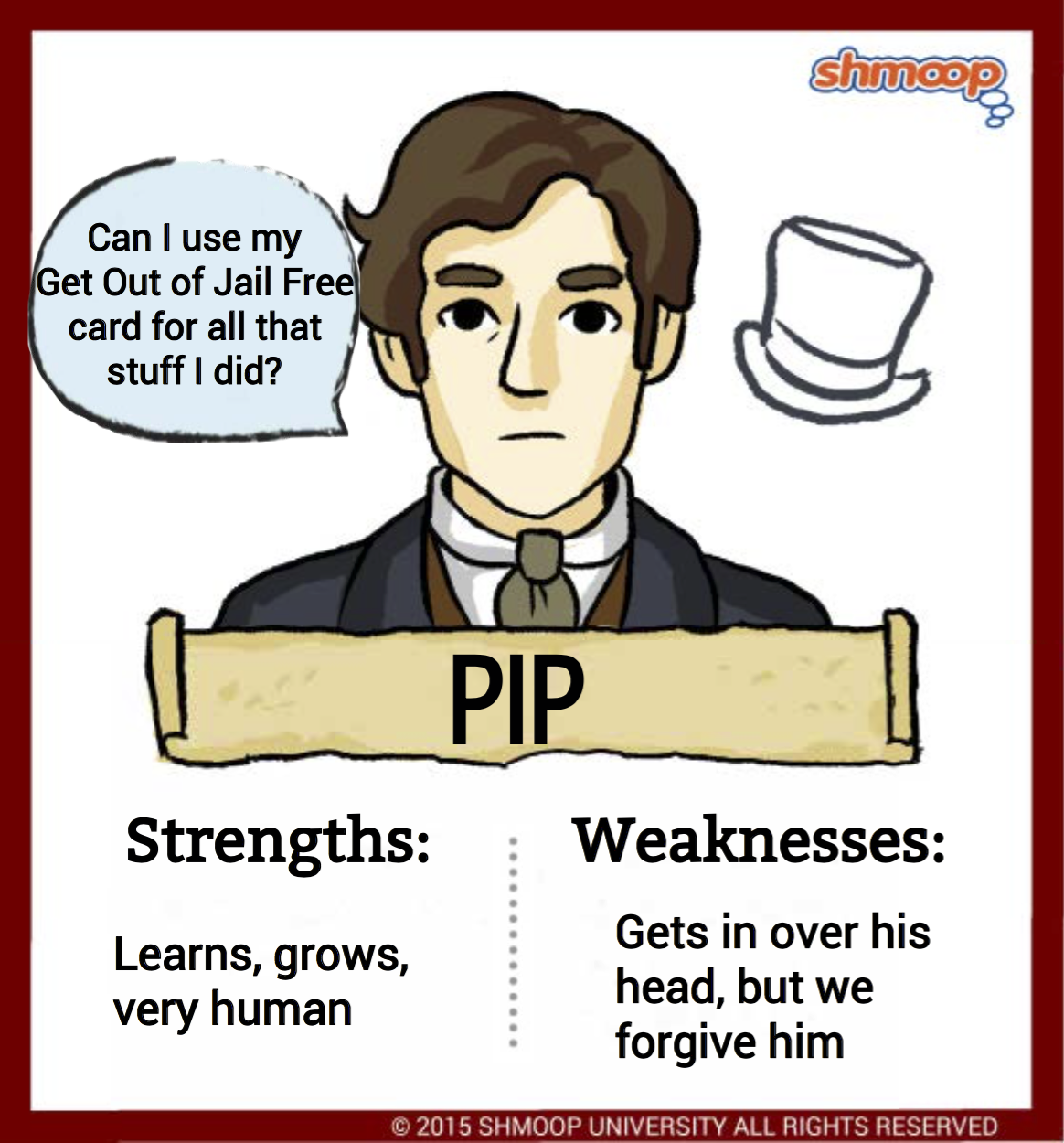

Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Pip is like that kid who goes away to college in the big city and comes back wearing designer shoes and thinking he's better than his parents because they don't know the difference between vermicelloni and bucatini. He's ungrateful, pretentious, snobbish, malcontent. He's ashamed of the man who loved and raised him; he's cruel to the girl who likes him; he throws himself after someone who repeatedly insists that she'll never be interested; and he's patronizing to his friends.

We also can't help liking him.

Pip the Little Boy

See, we've known Pip since he was a little boy being abused by his sister. We have much stricter standards about child abuse these days, but even in a century when it was common to use physical punishment, Pip's upbringing is particularly bad. He tells us himself, from his adult-narrator perspective:

My sister's bringing up had made me sensitive. In the little world in which children have their existence whosoever brings them up, there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injustice. It may be only small injustice that the child can be exposed to; but the child is small, and its world is small, and its rocking-horse stands as many hands high, according to scale, as a big-boned Irish hunter. (8.95)

We get a lot of this child's perspective in the first few chapters of the book. We see the world from Pip's viewpoint, like the "fearful man" (1.4) who accosts him, or the way he "twist[s] the only button on [his] waistcoat round and round" when he hears that his sister has the "Tickler" with her (8). But mostly we hear that he's afraid. Pip seems to spend his entire life being frightened and terrified—of his sister, of the convict, of the convict's supposed friend, and even of himself, "from whom an awful promise had been extract" (61).

Terrified or not, Pip steals the food and file that the convict asks for—and here's where we see the little hints of his character that make us keep liking him, even when he grows up to be a big dummy. Pip may be terrified, but he still manages to "pity" the convict's "desolation" and ask him if he's enjoying his meal (22).

That moment of pity is super important. The same pity makes him help Magwitch years later, and the same pity makes him forgive Estella and Havisham, and the same pity makes us, well, pity him instead of hate him.

Pip the Malcontent

Also, truth: what Miss Havisham and Estella do to Pip is just mean. When the story opens, he's a happy (if scared) little boy, who's looking forward to growing up and working on the forge with Joe. And then Miss Havisham descends on him like, well, an avenging spirit and wrenches him away from his little marshy idyll:

I had never parted from him before, and what with my feelings and what with soap-suds, I could at first see no stars from the chaise-cart. But they twinkled out one by one, without throwing any light on the questions why on earth I was going to play at Miss Havisham's, and what on earth I was expected to play at. (7.91)

In one late-night cart ride, Pip is leaving Joe and his childhood behind, and he hasn't even met Miss Havisham yet. Once he does, his happy—or at least innocent—days are behind him, because for the first time he meets people who are different. He realizes that there's a world beyond the village, and that not everyone is like him and his family.

It's a scary realization for anyone, and you have to remember that we're working with pretty strict class boundaries here. Most people these days still tend to marry within their socioeconomic group, but it's certainly not out of the question to marry someone who grew up much richer or poorer than you did, and lots of people have friends who are from different backgrounds.

Not in an English village of the nineteenth century. These are literally the first people Pip has ever met who aren't like him, and it doesn't end well. Estella calls him common, makes fun of his language and his boots and his hands, and from that exact moment Pip is discontented. He can't get her words out of his mind:

that I was a common labouring-boy; that my hands were coarse; that my boots were thick; that I had fallen into a despicable habit of calling knaves Jacks; that I was much more ignorant than I had considered myself last night, and generally that I was in a low-lived bad way. (8.105)

So, here's another reason that we never end up hating Pip, even though he's totally asking for it: we feel sorry for him. And we totally get it. Every single one of us has been in a situation where we've met someone way cooler than us who made us feel bad about our clothes, our taste in music, or our celebrity crush. (Admit it: even you cool kids have been in this situation.)

Feeling like that can make people do pretty dumb things—like telling their friends, "I want to be a gentleman" (17.24), or being "ashamed" of their parents/guardians. Think being embarrassed by your folks is something your generation invented? Nuh-uh. Just introducing Joe to Miss Havisham gives Pip a "strong conviction that [he] should never like Joe's trade" (13.69). And the worst part is that, if he'd never met Estella, he wouldn't care: "what would it signify to me, being coarse and common, if nobody had told me so" (17.33).

Yeah. We can forgive Pip a lot.

Pip the Gentleman

And that's good, because we have an awful lot to forgive. Once he starts getting educated he gets, well, insufferable. He tries to "impart" knowledge to Joe to make him "less ignorant and common" (15.20), he patronizes Biddy, and he generally acts like he's too good for anything.

So, here's something to think about: if you weren't reading carefully, you might think that Dickens was really down on self-improvement. But we don't think that's true. Both Biddy and Joe end up learning stuff—Biddy learns whatever Pip does, and then she teaches Joe to write—but neither of them lets it go to their heads. Only Pip does.

The problem is that Pip has all the wrong ideas about being a gentleman. He sees it as all about surface and appearance: having the right clothes, hiring a servant, spending money in the right places, and having the right friends. But he's fooling himself—something even Estella sees when she says that "you made your own snares. I never made them" (44.22).

See, being a gentleman is much more about what's inside than what's outside, and Pip doesn't learn that until much, much later. In fact, he doesn't learn it until he almost loses everything.

No Expectations

When Pip first finds out that Magwitch and not Miss Havisham is his benefactor, it almost destroys him:

Miss Havisham's intentions towards me, all a mere dream; Estella not designed for me; I only suffered in Satis House as a convenience, a sting for the greedy relations, a model with a mechanical heart to practise on when no other practice was at hand; those were the first smarts I had. (39.98)

Pip has no girlfriend and no fortune—since he feels like he can't accept Magwitch's—but he does gain something from this realization: he gains self-respect. Sure, he considers just running away from everything. But he doesn't. Just like that scared little boy on the marshes almost twenty years ago, he has compassion for a fellow human-being. That's the compassion and pity that we liked in the little boy, and it helps him become a true gentleman.

So, what are the acts of a true gentleman? He helps Magwitch hide and plots his escape; he braves Miss Havisham to ask for money to help set up Herbert Pocket as a partner in a shipping firm; and he has the self-control to be happy for Joe and Biddy—and the grace to move himself away from London and dedicate himself to paying them back.

It looks like being a gentleman is much more about grace, pity, self-control and compassion than having nice boots and soft hands.

Pip the Lover

Let's take a look at one last speech—maybe the most important thing that Pip says in the whole novel. It's his farewell speech to Estella, when he learns that she's marrying Drummle:

"Out of my thoughts! You are part of my existence, part of myself. You have been in every line I have ever read, since I first came here, the rough common boy whose poor heart you wounded even then. […] Estella, to the last hour of my life, you cannot choose but remain part of my character, part of the little good in me, part of the evil. But, in this separation I associate you only with the good, and I will faithfully hold you to that always, for you must have done me far more good than harm, let me feel now what sharp distress I may. O God bless you, God forgive you!" (44.70)

Pip may not quite have finished his whole growing up, but he's getting close: he "forgives" Estella, and he says that she's done him "far more good than harm." But is this true? He's said more than once that he wishes he'd never met Miss Havisham or gone to Satis House, but now he seems to have changed his mind. Is Pip better off at the end of the novel?

Pip the Grownup

One way of thinking about this is through Joe. Now, Joe's a good guy. He's kind, cheerful, dutiful, hard-working, and loving. But—and we just have to say this—we're not sure he's really an adult in the sense that Dickens means it. Pip even thinks of him as a child at the beginning of the novel. Sure, he has some hard times, what with his wife dying and his adopted son rejecting him. But through it all, Joe himself never changes, never experiences (that we know about) a crisis of self-identity that leaves him sadder and wiser.

Not Pip. He goes from a contented little laboring boy to a discontented adolescent to a resigned and hard-working man. At the end, he tells Estella, "I work pretty hard for a sufficient living, and therefore—yes, I do well" (59.53).

We hate to break it to you, Shmoopers, but for most of us, that's what growing up means: realizing that our great expectations aren't going to come true, and that, instead of becoming rock stars or presidents, we'll spend most of our lives working hard for a sufficient living—just like Pip.

Pip's Timeline