What are Infectious Diseases?

As you might suspect, infectious diseases are caused by things that infect or invade the body. Ten points if you knew that already (only five if you just read it a minute ago in the introduction). These tiny harmful infectious invaders are called pathogens, and the organism being infected is called the host. This is not the same as hosting a big party. When your body becomes the unwilling host for a pathogen, it can be very dangerous.

The sickness that the pathogen causes when it infects the host is the infectious disease. Each pathogen causes a different disease, and the symptoms of the disease can vary depending on the host being infected. Some common types of pathogens are:

To begin with, there are genetic diseases (or genetic disorders). These are diseases caused by your genetic makeup and are NOT cause by any pathogen. Since they are not infectious diseases, you cannot "catch" a genetic disease. People with a genetic disease such as Down's syndrome are born that way.

Most conditions a baby is born with are genetic disease and NOT infectious diseases. However, it IS possible to be born with an infectious disease. This just means that the baby was infected by a pathogen while it was inside the womb or during birth.Diseases like cancer and diabetes are also NOT infectious diseases. They are likely a combination of genetic components and environmental components. You cannot "catch" cancer or diabetes because they are not caused by pathogens.

Although cancer is not an infectious disease, some infectious diseases can cause cancer. For example, Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) is known to be related to cervical cancer, but infection with HPV does not mean that you currently have or ever will have cervical cancer. The cancer is just much more likely to occur with certain types of HPV infections.

Bacteria are found all over the place. You come into contact with them every minute of every day. You can find them in your environment (both in nature and on man-made surfaces), in your food, and by coming into contact with an infected person or animal. About 80% of infections are spread by hand to hand contact or hand to object contact. In fact, your keyboard and mouse are probably covered in bacteria like the one shown below, but don't worry. Most of the bacteria we encounter are non-pathogenic which means they do not cause disease. We will discuss bacteria more in a later section.

Pseuomonas aeruginosa bacteria which has been found on computer keyboards. Image from here.

Viruses need a living host to replicate, but some viruses can still survive for a period of time outside of a host. We can become infected with viruses the same way we get infected by bacteria. However, some types of viruses cannot survive outside a host and can only be transmitted in bodily fluids like blood or semen. We will discuss viruses more in a later section.

Lymph nodes are basically local branch offices of the immune system. When a pathogen is detected nearby, the local office starts bustling with activity, causing the lymph node to become enlarged. When a doctor touches the sides of your throat he or she is checking for how busy your lymph nodes are. Just like at the lymph node, the rush of immune cells to the battle site can cause inflammation such as swelling, tenderness, redness, and heat. The entire body can also raise its temperature in order to try and kill the invader. This causes a fever. The alarm from the patrol cell also signals the body to build up an army of antibodies. Antibodies are designed to detect one specific pathogen, and an entire army is created just to help detect and assist with the destruction of that one specific kind of pathogen.When the battle is over, a small militia group of antibodies is left to keep guard just in case the pathogen ever dares to return. This is why you don't get sick with something the second time that you catch it. The militia is already in place and the immune system can be activated quickly.

1) It does not get into your body because your skin and mucus membranes prevent it from getting inside.

2) The pathogen enters the body through a cut or a natural opening, but it is detected and killed by your immune system before it can replicate and cause trouble.

3) The pathogen gets inside your body and sets up camp, but doesn't cause any major problems. If this happens, the pathogen might not even be considered a pathogen if it's not causing trouble. We will discuss this topic more in the "Helpful Bacteria" section.

4) The pathogen gets inside and replicates and causes an infectious disease.

As this is an infectious disease chapter, we will focus more on what happens after the 4th option.

Sometimes it is easiest to look for a pathogen by texting the immune system and asking if they have seen it. Well, not quite. Like your great-grandmother, the immune system still doesn't text, but lab workers can look for antibodies against different pathogens. If you have a lot of antibodies it means you are currently infected. If you only have a few (militia) antibodies then you were probably infected in the past.

We can't change our genetic makeup, or prevent a disease whose cause is unknown, but if we prevent ourselves from becoming infected by a pathogen then we will never have an infectious disease. It sounds simple, but the bad news is that you will have to live a life of solitude in sterile isolation. It is impossible to live in today's society without encountering pathogens. Take a look at a real-case of someone trying to never encounter a pathogen: David, the boy in a bubble. However, there are many ways to limit the chances of dangerous infection, such as:

If a disease can affect humans and other animals it is called a zoonotic disease. As we learn about different types of diseases, be on the lookout for which pathogens cause zoonotic diseases.

Sometimes an animal can be infected by a pathogen but not get sick by it even though it makes other animal species sick. An animal like this is called a vector or a carrier. This means that although they are not sick, they can carry the pathogen to other species that do get sick. They can even spread the disease more than a sick person or animal because they are healthy enough to travel here there and everywhere carrying the bug with them. How rude.

There are special government organizations set up to investigate disease outbreaks. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is in charge of investigating diseases in the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) follows outbreaks all over the planet. For more information on infectious diseases you can contact these organizations.

If a disease affects a large amount of people on many continents then it is called a pandemic. Today, the WHO is in charge of determining if something is an official pandemic based on how many people are sick with the infectious disease, where they live, and how deadly the infection is. Throughout history there have been many stories and records of epidemics or pandemics. These were two of the worst:

Black Death (or Bubonic plague or Infection with Yersinia pestis)

In the late 1300's an infectious disease swept across Europe and the Middle East and killed an estimated 75-200 million people. That is like one to two thirds of the population of the United States today, but back then it was likely half of the population in all of Europe and one third of the population in the Middle East. Yowzers.

It was called the Black Death or bubonic plague, and it was caused by an infection with the bacteria Yersinia pestis. This little bacterium was carried by fleas riding on the rat transportation system (this was before the subway). When the fleas bit the humans, the bacteria infection began and often ended 2-7 days later with death.

Yersinia pestis bacteria inside a flea. Image from here.

1918 Spanish Influenza

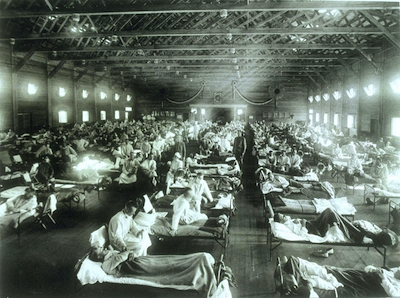

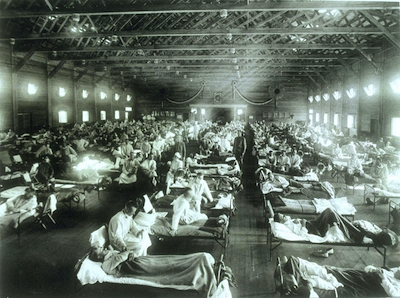

In 1918 an infectious disease spread around the globe and killed 50-100 million people. That is nearly four times the number of people killed in WWI. It spread directly from person to person, and was caused by the Influenza A virus.

The infection was most severe in the lungs which caused victims to cough. When they coughed, they released virus into the air in tiny aerosol particles. These were inhaled by people around them, and the disease spread and spread and spread. It is estimated that 20% of the humans on the planet became infected and that the infection was fatal 10-20% of the time. Adjusted for 2013 population, that would mean 1.4 billion people would become infected and 280 million people would die if this happened today.

A hospital ward at Camp Funston, Kansas for treating the massive numbers of patients infected with 1918 Spanish influenza. Image from here.

A biological agent can be extremely deadly or incapacitating. It can spread quickly through a population, causing widespread effects. It can also have little effect on the perpetrator if they take precautionary drugs or maintain a safe distance. It can also be secretly distributed leaving little evidence to trace the bioweapon back to the perpetrator.

https://media1.shmoop.com/images/biology/biobook_infectdis_graphik_5.png

Biohazard symbol. Sometimes it is a yellow symbol on a red background.

Using biological agents as weapons is not a new concept. Legend tells us that plague-infected bodies were sometimes catapulted over fortress walls during battles in the middle-ages. Later, during the French and Indian war, British troops were said to have intentionally infected Native Americans with smallpox by giving them infected blankets or handkerchiefs as a false peace offering.

As knowledge about infectious diseases has increased over time, so has the interest in weaponizing them. Due to the use of chemical weapons in World War I, the Geneva protocol prohibited the use of biological and chemical substances in 1925. This protocol, however, did not prevent the possession and development of such weapons.

This loophole meant that throughout the 20th century various countries and groups conducted secret testing of biological agents in hopes of creating bio-weapons. From 1936-1945 the Japanese government set up a special group, Unit 731, to study biological and chemical weapons. It's possible that hundreds of thousands of unwilling prisoners of war and civilians of Japanese-occupied territories were purposely infected and killed with the plague, anthrax, cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, and other pathogens. Later, during the Cold War, both the United States and Soviet labs also raced to develop bio-weapons.

Luckily, several countries came to their senses and in 1972 the United Nations Biological Weapons Convention was drawn up. Currently, 165 member states-parties are members of this convention.

Map showing the states/parties (in blue) that are members of the Biological Weapons Convention as of 2007. Image from here.

While it is good that biowarfare is not allowed by most countries, the current threat is bioterrorism. There is still a strong threat that terrorist groups will develop and use bioweapons. In 1984, a group sprinkled Salmonella bacteria over local salad bars resulting in 750 cases of food poisoning in Oregon. Luckily, nobody died, but dust was the main item in many salad bars for quite awhile afterwards due to fear.

In 2001, bioterrorism struck again when seven letters containing Anthrax bacteria were mailed to two Senators and five media outlets in the United States. The origin of those letters was never determined, although it is known that the strain of Anthrax was similar to a strain which was kept at the United States Amy Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases. Five people died in these attacks.

The sickness that the pathogen causes when it infects the host is the infectious disease. Each pathogen causes a different disease, and the symptoms of the disease can vary depending on the host being infected. Some common types of pathogens are:

- bacteria

- viruses

- fungi

- parasites

What Aren't Infectious Diseases?

Sometimes it is helpful to understand something by explaining what it is not. Think about which diseases are NOT infectious.To begin with, there are genetic diseases (or genetic disorders). These are diseases caused by your genetic makeup and are NOT cause by any pathogen. Since they are not infectious diseases, you cannot "catch" a genetic disease. People with a genetic disease such as Down's syndrome are born that way.

Most conditions a baby is born with are genetic disease and NOT infectious diseases. However, it IS possible to be born with an infectious disease. This just means that the baby was infected by a pathogen while it was inside the womb or during birth.Diseases like cancer and diabetes are also NOT infectious diseases. They are likely a combination of genetic components and environmental components. You cannot "catch" cancer or diabetes because they are not caused by pathogens.

Although cancer is not an infectious disease, some infectious diseases can cause cancer. For example, Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) is known to be related to cervical cancer, but infection with HPV does not mean that you currently have or ever will have cervical cancer. The cancer is just much more likely to occur with certain types of HPV infections.

How Can Someone Get an Infectious Disease?

The ONLY way to get an infectious disease is to be infected by the pathogen that causes that particular disease. These pathogens enter your body through natural openings, like your mouth or your nose, or through unnatural openings, like a paper cut or a zombie bite. Since most pathogens are too small to be seen with the naked eye, most of the time you will not even know that you have been infected until you start showing symptoms of disease. Well, that is, if you start showing symptoms. The immune system is an awesome defensive force and just might take care of things before you notice them. This is a good thing because pathogens are lurking EVERYWHERE!Bacteria are found all over the place. You come into contact with them every minute of every day. You can find them in your environment (both in nature and on man-made surfaces), in your food, and by coming into contact with an infected person or animal. About 80% of infections are spread by hand to hand contact or hand to object contact. In fact, your keyboard and mouse are probably covered in bacteria like the one shown below, but don't worry. Most of the bacteria we encounter are non-pathogenic which means they do not cause disease. We will discuss bacteria more in a later section.

Pseuomonas aeruginosa bacteria which has been found on computer keyboards. Image from here.

Viruses need a living host to replicate, but some viruses can still survive for a period of time outside of a host. We can become infected with viruses the same way we get infected by bacteria. However, some types of viruses cannot survive outside a host and can only be transmitted in bodily fluids like blood or semen. We will discuss viruses more in a later section.

How Does the Immune System Detect and Fight Pathogens?

The human immune system is excellent at detecting and destroying most invaders before they can cause any major trouble (unless it is the zombie virus, which is obviously unstoppable). The first defense is your skin and your mucus membranes (like the inside of your nose and mouth). They act like a barrier to keep things out. You are most vulnerable to infections when you have a break in these defensive layers.The next layer of defense is a patrol of immune cells that travels around the body looking for anything suspicious. If they find something, they sound the alarm, causing some larger cells to come eat at the invader buffet. They can also bring the intruder to one of the body's lymph nodes where lots of immune cells hang out for further inspection.Lymph nodes are basically local branch offices of the immune system. When a pathogen is detected nearby, the local office starts bustling with activity, causing the lymph node to become enlarged. When a doctor touches the sides of your throat he or she is checking for how busy your lymph nodes are. Just like at the lymph node, the rush of immune cells to the battle site can cause inflammation such as swelling, tenderness, redness, and heat. The entire body can also raise its temperature in order to try and kill the invader. This causes a fever. The alarm from the patrol cell also signals the body to build up an army of antibodies. Antibodies are designed to detect one specific pathogen, and an entire army is created just to help detect and assist with the destruction of that one specific kind of pathogen.When the battle is over, a small militia group of antibodies is left to keep guard just in case the pathogen ever dares to return. This is why you don't get sick with something the second time that you catch it. The militia is already in place and the immune system can be activated quickly.

What Will Happen If I Meet a Pathogen Today?

As a human you encounter many types of pathogens in your environment every day. When you meet one on the street one of four things can typically happen:1) It does not get into your body because your skin and mucus membranes prevent it from getting inside.

2) The pathogen enters the body through a cut or a natural opening, but it is detected and killed by your immune system before it can replicate and cause trouble.

3) The pathogen gets inside your body and sets up camp, but doesn't cause any major problems. If this happens, the pathogen might not even be considered a pathogen if it's not causing trouble. We will discuss this topic more in the "Helpful Bacteria" section.

4) The pathogen gets inside and replicates and causes an infectious disease.

As this is an infectious disease chapter, we will focus more on what happens after the 4th option.

I Feel Sick. How Can I Tell If I Have an Infectious Disease?

The only way to know for sure if you have an infectious disease is to see a doctor who will order some lab tests. Sometimes the lab workers will look directly for the pathogen by checking your blood, mucus, or other samples under a microscope. Other times they use special testing kits that can check for a specific pathogen if the doctor has a possible suspect in mind.Sometimes it is easiest to look for a pathogen by texting the immune system and asking if they have seen it. Well, not quite. Like your great-grandmother, the immune system still doesn't text, but lab workers can look for antibodies against different pathogens. If you have a lot of antibodies it means you are currently infected. If you only have a few (militia) antibodies then you were probably infected in the past.

How Can I Prevent an Infectious Disease?

All we have to do to prevent an infectious disease is…not get infected with the pathogen that causes it.We can't change our genetic makeup, or prevent a disease whose cause is unknown, but if we prevent ourselves from becoming infected by a pathogen then we will never have an infectious disease. It sounds simple, but the bad news is that you will have to live a life of solitude in sterile isolation. It is impossible to live in today's society without encountering pathogens. Take a look at a real-case of someone trying to never encounter a pathogen: David, the boy in a bubble. However, there are many ways to limit the chances of dangerous infection, such as:

- Frequent hand washing

- Covering coughs and sneezes

- Washing produce before eating it

- Adequately cooking and/or refrigerating meats and dairy products

- Getting vaccinated

- Using protection during sex

Infectious Diseases in Animals and Plants

Pathogens are very specific about which hosts they infect. Some diseases only affect plants. Other diseases only affect animals. Plant and animal diseases can be very dangerous for crops and livestock. The world's food supply can be severely damaged by a deadly plant or animal disease (the potato blight that devastated Ireland in the 1840's was caused by a deadly infectious disease).If a disease can affect humans and other animals it is called a zoonotic disease. As we learn about different types of diseases, be on the lookout for which pathogens cause zoonotic diseases.

Sometimes an animal can be infected by a pathogen but not get sick by it even though it makes other animal species sick. An animal like this is called a vector or a carrier. This means that although they are not sick, they can carry the pathogen to other species that do get sick. They can even spread the disease more than a sick person or animal because they are healthy enough to travel here there and everywhere carrying the bug with them. How rude.

Historic Epidemics and Pandemics

Throughout history, terrible infectious diseases have wreaked havoc on society. If an infectious disease affects a large amount of people in one area it is called an epidemic. The study of the effects of disease on a population is called epidemiology (pronounced ep-ih-deem- ee- ol-o-gee).There are special government organizations set up to investigate disease outbreaks. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is in charge of investigating diseases in the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) follows outbreaks all over the planet. For more information on infectious diseases you can contact these organizations.

If a disease affects a large amount of people on many continents then it is called a pandemic. Today, the WHO is in charge of determining if something is an official pandemic based on how many people are sick with the infectious disease, where they live, and how deadly the infection is. Throughout history there have been many stories and records of epidemics or pandemics. These were two of the worst:

Black Death (or Bubonic plague or Infection with Yersinia pestis)

In the late 1300's an infectious disease swept across Europe and the Middle East and killed an estimated 75-200 million people. That is like one to two thirds of the population of the United States today, but back then it was likely half of the population in all of Europe and one third of the population in the Middle East. Yowzers.

It was called the Black Death or bubonic plague, and it was caused by an infection with the bacteria Yersinia pestis. This little bacterium was carried by fleas riding on the rat transportation system (this was before the subway). When the fleas bit the humans, the bacteria infection began and often ended 2-7 days later with death.

Yersinia pestis bacteria inside a flea. Image from here.

1918 Spanish Influenza

In 1918 an infectious disease spread around the globe and killed 50-100 million people. That is nearly four times the number of people killed in WWI. It spread directly from person to person, and was caused by the Influenza A virus.

The infection was most severe in the lungs which caused victims to cough. When they coughed, they released virus into the air in tiny aerosol particles. These were inhaled by people around them, and the disease spread and spread and spread. It is estimated that 20% of the humans on the planet became infected and that the infection was fatal 10-20% of the time. Adjusted for 2013 population, that would mean 1.4 billion people would become infected and 280 million people would die if this happened today.

A hospital ward at Camp Funston, Kansas for treating the massive numbers of patients infected with 1918 Spanish influenza. Image from here.

Bioterrorism/Biowarfare

Nobody likes to think about weapons (except maybe Dr. Evil), but take a moment to think about what makes a good weapon. Deadly? Widespread destruction? No effect on the user? Secretive? It is for these reasons that many groups have sought to use infectious diseases as weapons. A weapon made out of a pathogen is called a biological weapon or bioweapon.A biological agent can be extremely deadly or incapacitating. It can spread quickly through a population, causing widespread effects. It can also have little effect on the perpetrator if they take precautionary drugs or maintain a safe distance. It can also be secretly distributed leaving little evidence to trace the bioweapon back to the perpetrator.

https://media1.shmoop.com/images/biology/biobook_infectdis_graphik_5.png

Biohazard symbol. Sometimes it is a yellow symbol on a red background.

Using biological agents as weapons is not a new concept. Legend tells us that plague-infected bodies were sometimes catapulted over fortress walls during battles in the middle-ages. Later, during the French and Indian war, British troops were said to have intentionally infected Native Americans with smallpox by giving them infected blankets or handkerchiefs as a false peace offering.

As knowledge about infectious diseases has increased over time, so has the interest in weaponizing them. Due to the use of chemical weapons in World War I, the Geneva protocol prohibited the use of biological and chemical substances in 1925. This protocol, however, did not prevent the possession and development of such weapons.

This loophole meant that throughout the 20th century various countries and groups conducted secret testing of biological agents in hopes of creating bio-weapons. From 1936-1945 the Japanese government set up a special group, Unit 731, to study biological and chemical weapons. It's possible that hundreds of thousands of unwilling prisoners of war and civilians of Japanese-occupied territories were purposely infected and killed with the plague, anthrax, cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, and other pathogens. Later, during the Cold War, both the United States and Soviet labs also raced to develop bio-weapons.

Luckily, several countries came to their senses and in 1972 the United Nations Biological Weapons Convention was drawn up. Currently, 165 member states-parties are members of this convention.

Map showing the states/parties (in blue) that are members of the Biological Weapons Convention as of 2007. Image from here.

While it is good that biowarfare is not allowed by most countries, the current threat is bioterrorism. There is still a strong threat that terrorist groups will develop and use bioweapons. In 1984, a group sprinkled Salmonella bacteria over local salad bars resulting in 750 cases of food poisoning in Oregon. Luckily, nobody died, but dust was the main item in many salad bars for quite awhile afterwards due to fear.

In 2001, bioterrorism struck again when seven letters containing Anthrax bacteria were mailed to two Senators and five media outlets in the United States. The origin of those letters was never determined, although it is known that the strain of Anthrax was similar to a strain which was kept at the United States Amy Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases. Five people died in these attacks.