ShmoopTube

Where Monty Python meets your 10th grade teacher.

Search Thousands of Shmoop Videos

Literature Videos

They say that honesty is the best policy, but Jack lies about his identity and still gets the girl. Does that mean we should all lie to get what we want? Not so much.

17th-Century Literature Videos 1 videos

Love potions are tricky business (not that we've ever tried using one, of course). They can make you fall in love with the wrong person…or, in th...

18th-Century Literature Videos 9 videos

And you thought a nymph was a naturally lovely woodland creature. To be fair, so did we. But boy did Jonathan Swift prove us wrong.

We were so moved by Angelina Jolie's overseas adoptions that we created a proposal to bring foreign-born children over by the thousands! Think abou...

The Constitution of the United States is the highest law in the land: it's a written statement of the core principles of the American government. I...

19th-Century Literature Videos 51 videos

How did Scrooge go from being naughty to nice so quickly, and why? (Hint: contrary to popular belief, it has nothing to do with the ghost of Santa...

What would YOU do if the heart of the person you buried under the floorboards started making noise? Only one way to find out... (Note: Shmoop does...

Oh, William Lloyd Garrison and his radical ideas... like... you know... freedom and equality. Weird, right?

20th-Century Literature Videos 7 videos

When you think about it, chess could be a metaphor for just about anything, really.

Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man is an American classic. Hope you're not expecting any exciting shower scenes though. It's not that kind of book.

Do not go gentle into that good night. In fact, if it's past your curfew, don't go at all into that good night. You just stay in your good bed and...

21st-Century Literature Videos 16 videos

Sorry, guys: this novel doesn't follow the dramatic life events of pumpkin pie, nor does it explore what it truly means to be the mathematical cons...

We volunteer you as tribute to watch this video analysis of Katniss in the second book of the Hunger Games series. After the berry suicide attempt...

“Happy Hunger Games!” Or not. Katniss’s Hunger Games experiences left a not-so-happy effect on her. This video will prompt you to ponder if...

American Literature Videos 215 videos

“Happy Hunger Games!” Or not. Katniss’s Hunger Games experiences left a not-so-happy effect on her. This video will prompt you to ponder if...

Who's really the crazy one in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest? Shmoop amongst yourselves.

Sure, Edgar Allan Poe was dark and moody and filled with teenage angst, but what else does he have in common with the Twilight series?

Beowulf Videos 9 videos

Old English is just English, right? Can’t be more difficult than reading Shakespeare, right? Hah. Yeah...no. Click on the video to find why tra...

Who is it about? Who told it? Who wrote it? Who are we? What’s the meaning of life? Do you know the Muffin Man? All these answers and more can be...

The characters in Beowulf knew the importance of bling. Watch the video to learn more about the place of material goods in the wonderful world of B...

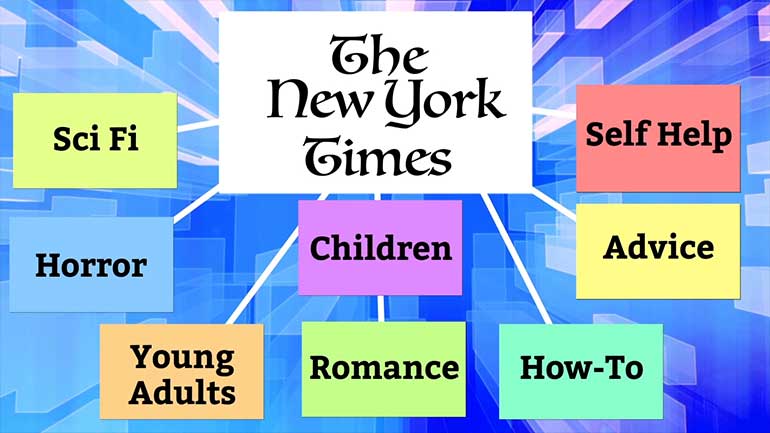

Bestsellers Videos 11 videos

"Come out, come out, wherever you are..." and watch this video about Stephen King's The Shining. After it's over, we may or may not axe you some qu...

British Literature Videos 176 videos

Meet Charles Darnay, the nobleman who spends more time on trial and in prison than attending balls and drinking expensive wine. Don't feel too bad...

Written in Anglo-Saxon, or Old English, sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries, Beowulf is an epic poem that reflects the early medieval warri...

Brave New World is supposed be an exciting book about a negative utopia and the corrupt powers of authority. So where’s the big car chase? What's...

Charles Dickens Videos 20 videos

Was the marriage plot a bunch of folks who schemed and conned their way into marriage? Hit play to find out.

How did Americans and Brits feel about Dickens' comedy? Eh...let's just say it was the best of comedy, it was the worst of comedy.

How has Dickens impacted culture today? We don't know about you, but we watch A Muppet's Christmas Carol every year, so...that's probably the answe...

Common Core Videos 2 videos

Common Core 8th Grade 1.3 Reading Literary Texts. Which evidence from the text best supports the inference that Gorgons are dangerous?

Whale, whale, whale...what have we got here? Looks like a question about what Kipling was trying to achieve in "How the Whale Got His Throat." Fun...

Contemporary Literature Videos 18 videos

Contemporary works of literature such as The Help reference important historical events in order to reflect on themes and challenges that have...

Does Prospero have magical powers? And if he does, could he get us into Hogwarts? We've been waiting so patiently...

On the road again...we just can't wait to get on the road again...and discuss On The Road.

Dracula Videos 16 videos

Vlad the Impaler was an appropriately named guy, until he went on tropical vacations. Then, he went by Vlad the Imtanner. For some facts that are a...

Readers may be already be familiar with Dracula, but what about the mathematician and author, Bram Stoker? And yes, he graduated with a degree in m...

Looks, wealth, and a super cool castle to live in… Well...maybe not live in, if you happened to be Dracula. But for the most part, this guy had...

Dystopian Literature Videos 33 videos

Well, if this book doesn't make you want to tape over your laptop camera, we don't know what will.

Imagine a world in which all literature was dystopian. Okay, so we may be getting to that point, 1984 and V for Vendetta helped start it all.

By the end of this video, you will be brainwashed. There's nothing you can do about it; we just wanted to let you know. We like to think we're bigg...

Early 20th-Century Literature Videos 47 videos

You might be hearing a chorus of farewells if you recommend A Farewell to Arms as the next read for your Fabulously Feisty Feminist Book Club.

She was just a girl who found herself in some unimaginably awful circumstances. If you feel like gaining some valuable perspective on the drama in...

Frankenstein Videos 17 videos

We’ll preface this video about Frankenstein’s preface by saying that Mary Shelley is an awesome woman, and she wants everybody to be aware. Che...

Is Victor Frankenstein a: Romantic Hero? b: Byronic Hero? c: Satanic Hero? d: Guitar Hero? All of the above (but maybe not D…) We don�...

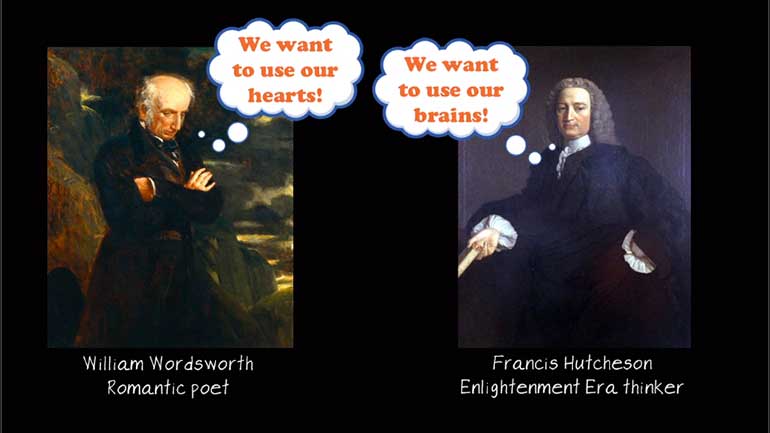

What is Gothic Romanticism? It's when two goths fall in love. Duh. Wait, that’s not what it is? Oh. We should probably watch the video and figure...

Hero's Journey Videos 14 videos

Join us for part one of the Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell. We'll find out who he is, what he's responsible for, and if he has anything to do with...

Join us for part two of the Hero's Journey: The Three Stages. It'll be way less fun than watching the Three Stooges.

Join us for part three of the Hero's Journey: Archetypes. Then, feel free to send us a letter about your favorite archetype, which we may or may no...

Literary Topics Videos 221 videos

Dr. Seuss was a failure to start, but he soon learned to follow his heart. He wrote books about things that he knew, and soon enough, his book sale...

Sure, Edgar Allan Poe was dark and moody and filled with teenage angst, but what else does he have in common with the Twilight series?

Literature en Español Videos 3 videos

Si alguna vez te encuentras en una balsa flotando en el río Mississippi, usted va a querer hacer algo. Lectura clásico de Mark Twain, Las aventur...

Moby-Dick - una ballena extraña. Nuestro amigo capitán Ahab la había perseguido para años, pero no es el mejor lider en el mundo. Piensas que p...

Moby-Dick Videos 9 videos

Whoa, fifty different ways to say the word “whale” just in the Preface? Something tell us we’re in for a whale of a time. Yeah, we know, th...

The combination of religious and seafaring imagery in Moby-Dick is just like the peanut butter and the chocolate in a Reese's Cup––you can’t...

Queequeg. Cool name, but is he a cool guy? Guess you’ll have to check out the video to find out. Because surprisingly enough, Googling, “is Q...

Oedipus Videos 6 videos

Post-1945 Literature Videos 13 videos

Well, if this book doesn't make you want to tape over your laptop camera, we don't know what will.

By the end of this video, you will be brainwashed. There's nothing you can do about it; we just wanted to let you know. We like to think we're bigg...

This video summarizes the play A Raisin in the Sun. It discusses the Youngers, members of an African-American family trying to better themselves wh...

Shakespeare Videos 53 videos

Aren't midsummer night dreams the worst? You wake up all sweaty and gross, and for a minute there, you can't even remember where you are. And also,...

Love potions are tricky business (not that we've ever tried using one, of course). They can make you fall in love with the wrong person…or, in th...

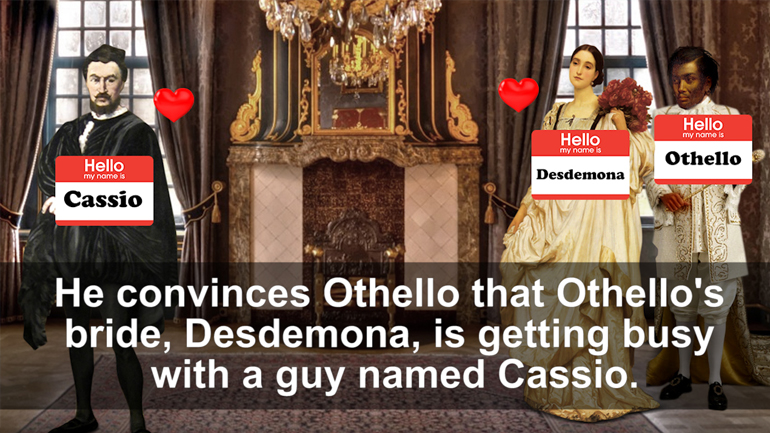

We're not sure if good ol' Shakespeare would endorse The Bachelor and The Bachelorette, but that's not going to stop us from hosting themed viewing...

Short Stories Videos 7 videos

This video defines symbolism and analyzes the use of symbolism in stories like The Great Gatsby and To Kill a Mockingbird. What effect do symbols h...

The micro setting: Enterprise. The macro setting: “Space, the Final Frontier!”

This video defines theme and investigates how it’s used in literature—is it intentional? In this video, we discuss the difference between theme...

Southern Gothic, Kafka, and Moby-Dick Videos 10 videos

Call me Shmoop...er, we mean, Ishmael. It’s time to catch a whale. ...Just kidding, we’ll read about it instead. The WWF told us we can’t d...

Ready for a horror story that isn’t about a bad hair day? Pick up a Southern Gothic novel like Moby-Dick or As I Lay Dying instead. Though now th...

Add half a cup of post-Civil War, a pinch of Reconstruction, a cup full of race issues, toss it in a Crock Pot called “The South,” and you’ve...

Speak Videos 16 videos

In High School we were usually told to "Make like a tree…" Melinda here has to make, like, a tree. Art stuff. We're painting with a broad-brush t...

Test Prep Videos 223 videos

AP English Literature and Composition 1.2 Passage Drill 4. As which of the following is the object being personified?

AP English Literature and Composition 1.4 Passage Drill 3. How is Burne's view of pacifism best characterized in lines 57 through 67?

AP English Literature and Composition 1.6 Passage Drill 5. Death is primarily characterized as what?

The Great Gatsby Videos 16 videos

It's the roaring 20s. A time of wealth, partying, and a huge inequality gap. Fun, fun, and, uh...not-so-fun. Hit play to discover more about the se...

East Egg: East coast, old money, and ponies. Maybe unicorns. Those snotty East Eggers won’t tell us anything. West Egg: West coast, new money, an...

Gatsby’s a man who throws huge parties and still has zero friends. Maybe they’re all like...Tupperware parties or something. Check out the vide...

The Narrative of Frederick Douglass Videos 15 videos

Frederick Douglass was an impassioned public speaker. So are we: we're impassioned about never speaking in public.

Why did Douglass write the book? Easy. Because TV wasn't a viable medium yet.

When we see it at the movies, our eyes roll. But are we guilty of the same? Shmoop!: The Movie, a Shmoop production, written by Shmoop, starring Sh...

The Road Videos 11 videos

Well, the world has ended, which is a total bummer. We didn’t even get a chance to sell our super valuable Beanie Baby collection. We hope you’...

The Road is full of emptiness and nobody knows where they’re going. So make a note to self, Shmoopers: when the apocalypse hits, grab a GPS.

Always read The Road with a dictionary at hand, because you’re going to need it. Seriously. We’re not known to be perfidious (though we do have...

Their Eyes Were Watching God Videos 10 videos

Free will vs. Predestination. One of the many interpretations for the title Their Eyes Were Watching God. We personally like, “Stop Staring at Me...

Their eyes might’ve been watching God, but our eyes are watching Zora Neal Hurston. Hit play to learn more about Hurston and the Harlem Renaissance.

Their Eyes Were Watching God is about Janie’s coming of age story towards the path of self-discovery, just like Luke from Star Wars. Seriously, J...

To Kill A Mockingbird Videos 15 videos

Were black people portrayed as stereotypes in To Kill A Mockingbird? Was Harper Lee trying to draw attention to the problems with stereotypes, or d...

Women's Literature Videos 37 videos

World Literature Videos 44 videos

Folk tales are all about conveying a deeper meaning—no banjos required. Arabian Nights is one of the most famous collections, so get ready to lea...

In Markus Zusak's The Book Thief, Death narrates the story of one girl who lived during the Holocaust. Not surprisingly, it's kind of a downer—bu...

Crime and Punishment is all about a boy killing for money, literally, and then spending the rest of the book trying to hide it. Although the book c...

![Quotes: And he said unto them, Ye will surely say unto me this proverb, Physician, heal thyself [...]](https://media1.shmoop.com/video/thumbnails/QUOTES_185_PHYSICIAN_HEAL_THYSELF%20770x433.jpg)