Viral Entry

Replication Cycle of a Virus

There are three major steps of a virus replication cycle. First, the virus has to get into a cell, then it has to replicate itself, then it has to get out. A virus would make a really good mafia hitman (get in, bada-bing bada-boom, get out). As we talked about in the previous section, there is a lot of diversity among viruses, and each virus group has devised a different strategy of entering a cell, replicating, and exiting a cell.

Replication of a Virus

Entry

The major barrier for virus entry into a cell is getting past the plasma membrane. As we talked about in the previous section, many viruses are surrounded by a lipid bilayer that is called an envelope. This is actually made from the plasma membrane of a previously infected cell. We like to think of enveloped viruses as a serial killer that makes masks from their previous victim. Which is why we get no sleep, and now neither will you.

Membrane Fusion of Viruses

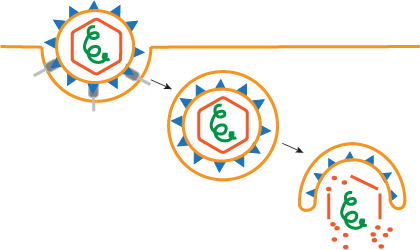

Enveloped viruses have evolved a strategy of getting into a cell using a process called membrane fusion. The membrane of the virus fuses with the plasma membrane of the cell into one single membrane that allows the virus to get into the cell. Think of it like when celebrities date, they no longer have separate identities. So, if Morgan Freeman were to date Olivia Newton John, they'd be called "Morgewton Freejohn."

It is the job of the viral membrane fusion glycoprotein to make this happen. Most viruses have only one glycoprotein that does this, while herpesviruses (the viruses that cause herpes, chicken pox, shingles, and "mono") and poxviruses use anywhere from 4-16 glycoproteins to perform this process.

Poxviruses are the group of viruses that includes the virus that cause smallpox. You might not know what this is as it was eradicated 30 years ago, and was one of the first and best examples of the efficiency of vaccines (see Vaccine section). If you want to know more about smallpox, ask your grandparents, as they'll be the last people to definitely know about it. But be warned, you'll probably have to eat a lot of hard candies in return for the information.

How does membrane fusion occur? Viruses have membrane fusion glycoprotein that change shape to fuse the virus and cell membrane. If you think of membrane fusion glycoproteins like taut rubber bands, they are just asking for some release from the tension of being pulled. The release in energy from a taut rubber band to a relaxed rubber band is what drives the membrane fusion process. What keeps Funions fresh so many days after you open it? The world may never know…

So, what is the trigger for this release of energy in the membrane fusion glycoprotein? It is usually one of two factors: low pH or binding a receptor. For some viruses, particularly retroviruses, it is a combination of both factors.

Endosomal Membrane Fusion

Low pH or endosomal entry of viruses requires virus binding to a cell through attachment of a virus protein to a receptor, or by spontaneously "sticking" cellular glycoproteins. The name glycoprotein comes from the many sugar groups that are attached to the protein. Just as wet sugar is very sticky, glycoproteins are also very sticky. So, virus sticking to a cell can be a specific or non-specific process, but virus receptor binding is always specific. But if you're sticky, take a shower.*

*We at Shmoop would like to apologize for that last joke. It was crude, and the writer has since been fired, and now is a KettleKorn salesman in Piscataway, NJ.

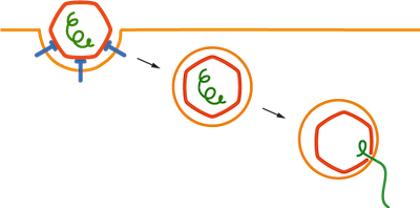

After attachment (binding to the cell), the cell internalizes the virus and sends it to a low pH compartment called an "endosome." This is a normal cellular process, and is how cells take in their environment for acquiring nutrients (think cellular "eating"). Once the virus gets into the low pH endosome, the low pH causes the glycoprotein to change shape and mediate membrane fusion.

Cell Surface Membrane Fusion

Many enveloped viruses do not enter through a low pH mechanism, and instead enter at the cell surface. In the case of these viruses, binding a cellular receptor is what triggers the change in the membrane fusion glycoprotein.

But what about naked viruses? They don't have envelopes, so how do they get across the plasma membrane? It is unclear how they actually get in the cell, but the best theory is that instead of triggering membrane fusion, low pH or receptor binding makes the capsid proteins of the naked viruses lodge themselves into the membrane to form a channel that allows the virus genome to enter the cell. Think of it like a naked guy showing up in your house. You're first thought it is ¬– how did he get here? You have some theories, but most likely it was the Craigslist ad that you answered.

Once the virus has entered the cell, if it still has capsid attached to the genome, it usually sheds this in a process called "uncoating." Just as it would be rude if you wear your coat around someone's house, the virus realizes it's rude to wear its coat in the cell, so it removes it before beginning replication. Some viruses keep their coat on a little bit longer than other viruses, as their coat helps find the nucleus and allows entry into the nucleus.