Diseases

In this section we’re going to take you on a miraculous journey from the sewers of London to suburban Connecticut as we explore how pathogenic bacteria spread and how they do what they do. It’s a veritable magic carpet ride—we’re surprised Disney hasn’t bought the rights yet. Okay, no. Not really. Disease isn’t pretty, but it’s filled with plot. It’s a war on a microscopic scale.

We’re going to be talking about infectious diseases that are caused by bacteria in this section. Infectious diseases are those that are spread by an infectious agent, such as a bacterium or virus. They’re different from other kinds of diseases, like the metabolic disease diabetes.

Many pathogenic bacteria secrete toxic molecules called exotoxins. Bacteria either release exotoxins into the extracellular environment or, alternatively, inject them directly into host cells.

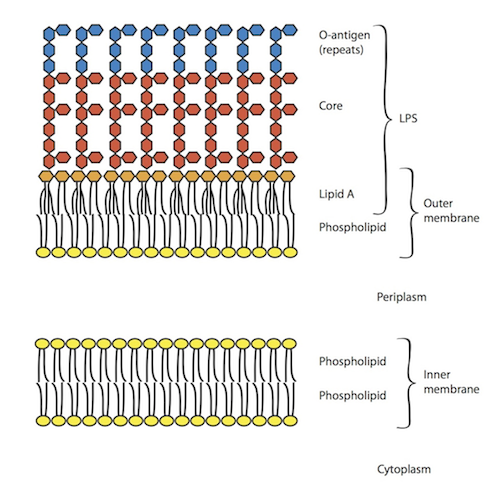

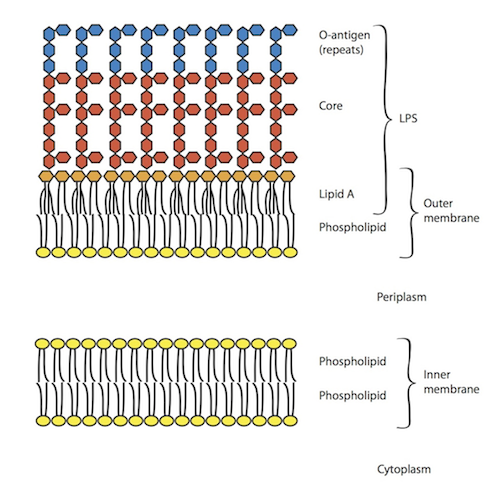

Serotyping depends on using antibodies that recognize the outermost regions of cells as well as released factors, including exotoxins. Just to review, in Gram-negative bacteria the outermost cell region is the outer membrane. Easy, right? The outer face of the outer membrane is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a compound made of lipid and sugars. Check. The part of LPS that reaches out away from the cell is called the O-antigen. The O-antigen is recognized by a lot of serotyping antibodies and can elicit a strong immune response.

The picture below shows where the O-antigen occurs on a normal, healthy cell. Since Gram-negative bacteria have an inner and outer membrane, both membranes are shown. The inside of the cell (cytoplasm) is at the bottom of the graph, while the outside of the cell is at the top.

The first membrane we come to, coming up, out of the cell is the inner membrane, which is made of two phospholipid layers. Two layers make a phospholipid bilayer. After we pass through the periplasm, we come to the outer membrane. The inner face of the outer membrane is again a phospholipid layer. The outer face, however, is LPS. LPS is made up of three components, lipid A (orange), the core (red), and the O-antigen (blue). The units of LPS are drawn as hexagons because they are sugars, which have a hexagon-like shape.

As drawn here, the outmost layer of LPS, the O-antigen, is four blue hexagons (sugars). These four sugars make up one unit of O-antigen. Cells have up to 40 units of O-antigen that go farther out into the area outside the cell. That was just too much for us to draw here!

When cells die and fall apart, these huge sugar chunks float out into the area around where the cells used to be. The immune response to O-antigen is so strong, that, given enough dying cells, and total craziness and pandemonium starts to happen. The body can induce a strong immunity response to O-antigen even though the bacteria are already dead. If the condition is severe enough it is known as septic shock and can result in death.

As the agents responsible for this toxic scenario, O-antigen and other immunogenic factors released by lysed bacteria are considered toxins. They’re called endotoxins rather than exotoxins, because they are a part of the cell, rather than secreted by it.

Then, we’d like to talk about a few other diseases (syphilis and Lyme diseases) with an eye towards different modes of transmission. Finally, we’re going to talk about a more recent application of Koch’s postulates towards understanding stomach ulcers.

The disease cholera almost always occurs following consumption of Vibrio cholerae-contaminated food or drinking water. Vibrio cholerae bacteria work their way to your intestines where they produce important virulence compounds.

Strains of Vibrio cholerae that can’t make the TCP pilus and/or cholera toxin are not pathogenic.

Over 3 million people a year are infected with Vibrio cholerae; most have mild symptoms, or not at all, but about one in ten require hospitalization. The biggest dangers of cholera lie in dehydration and salt loss due to diarrhea. Treatment is typically limited to rehydration and salt consumption. Nonetheless over 100,000 people die from cholera a year.

Cholera is spread through contaminated water, so it is rare in countries with clean drinking water supplies. Here’s a map of countries with cholera outbreaks in 2010 and 2011.

Treponema pallidum replicate rapidly at the site of infection, producing a lesion called a canker. They enter the bloodstream and then spread to other tissues. Syphilis becomes deadly when it reaches the brain.

Legionella bacteria enter the body through inhalation of small droplets in liquid (called aerosols) into the lungs. The disease was unknown until it first struck at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976. Just like John Snow tracked cholera to a contaminated well in London, scientists tracked the first Legionnaires’ disease outbreak to contaminated water in the cooling system of the convention hotel.

Marshall tried several different methods until he was able to culture enough of the bacteria, called Helicobacter pylori, to test if it caused ulcers. That’s right, he tested it Koch-style. Of course, it’s ethically challenging to hand human test subjects flasks of bacteria to see if they’ll give you an ulcer, so he tried it on himself. Think about that for a second. Would you catch yourself saying, "I’m going to drink this flask of bacteria…and if I’m lucky, just maybe I’ll get an ulcer at the end of it." Yeah, we probably wouldn’t say that either.

Marshall got his wish—and a Nobel Prize. Within a week, he began to develop stomach ulcers, and he saw an increase in the Helicobacter pylori in his stomach. Happily, antibiotic consumption killed off the bacteria in his stomach as well as those of other patients with ulcers. These other patients got the ulcers by the old fashioned way, which is still unknown. Stress and poor health habits are general risk factors for disease susceptibility. This may be especially true in the case of ulcers, where many people believed that ulcers were only caused by stress, with no infectious disease component.

• Cholera is typically spread by eating or drinking contaminated food or water

• Syphilis is spread by direct skin contact between hosts

• Lyme disease is spread by insect vectors (deer ticks)

• Legionnaires’ disease is spread by inhaling aerosols

Scientists are still investigating how Helicobacter pylori, which cause ulcers, are spread. Some scientists believe it is through saliva, while others believe it may be spread by flies.

Understanding the cause of disease affects how they are treated. Rather than focusing on antibiotics, regions with high rates of cholera should probably focus on their water supply, while communities with incidence of Lyme disease might want to look towards controlling the deer or tick population.

We’re going to be talking about infectious diseases that are caused by bacteria in this section. Infectious diseases are those that are spread by an infectious agent, such as a bacterium or virus. They’re different from other kinds of diseases, like the metabolic disease diabetes.

Virulence

Pathogenic bacteria are those that are capable of causing disease. Virulence factors are the components of cells, typically proteins, that make bacteria pathogenic. Small differences can make some strains of a species pathogenic, while the rest are not. In the first section, we mentioned that Vibrio cholerae has over 200 serotypes. Only two of those are known to be pathogenic.Many pathogenic bacteria secrete toxic molecules called exotoxins. Bacteria either release exotoxins into the extracellular environment or, alternatively, inject them directly into host cells.

Serotyping depends on using antibodies that recognize the outermost regions of cells as well as released factors, including exotoxins. Just to review, in Gram-negative bacteria the outermost cell region is the outer membrane. Easy, right? The outer face of the outer membrane is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a compound made of lipid and sugars. Check. The part of LPS that reaches out away from the cell is called the O-antigen. The O-antigen is recognized by a lot of serotyping antibodies and can elicit a strong immune response.

The picture below shows where the O-antigen occurs on a normal, healthy cell. Since Gram-negative bacteria have an inner and outer membrane, both membranes are shown. The inside of the cell (cytoplasm) is at the bottom of the graph, while the outside of the cell is at the top.

The first membrane we come to, coming up, out of the cell is the inner membrane, which is made of two phospholipid layers. Two layers make a phospholipid bilayer. After we pass through the periplasm, we come to the outer membrane. The inner face of the outer membrane is again a phospholipid layer. The outer face, however, is LPS. LPS is made up of three components, lipid A (orange), the core (red), and the O-antigen (blue). The units of LPS are drawn as hexagons because they are sugars, which have a hexagon-like shape.

As drawn here, the outmost layer of LPS, the O-antigen, is four blue hexagons (sugars). These four sugars make up one unit of O-antigen. Cells have up to 40 units of O-antigen that go farther out into the area outside the cell. That was just too much for us to draw here!

When cells die and fall apart, these huge sugar chunks float out into the area around where the cells used to be. The immune response to O-antigen is so strong, that, given enough dying cells, and total craziness and pandemonium starts to happen. The body can induce a strong immunity response to O-antigen even though the bacteria are already dead. If the condition is severe enough it is known as septic shock and can result in death.

As the agents responsible for this toxic scenario, O-antigen and other immunogenic factors released by lysed bacteria are considered toxins. They’re called endotoxins rather than exotoxins, because they are a part of the cell, rather than secreted by it.

Bacterial Diseases

We could write volumes and volumes of details about bacterial diseases, and scientists are learning more about them every day. What we’re going to do here is talk about one disease first, cholera. We’re going to talk about how the disease cholera depends upon virulence factors like we mentioned above.Then, we’d like to talk about a few other diseases (syphilis and Lyme diseases) with an eye towards different modes of transmission. Finally, we’re going to talk about a more recent application of Koch’s postulates towards understanding stomach ulcers.

Cholera

Earlier, we mentioned John Snow’s investigation of a cholera outbreak in London. Cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Vibrio cholerae is a curved, rod-shaped bacterium that lives in contaminated water. Remember, John Snow traced the infection to sewage leaking into a water source.The disease cholera almost always occurs following consumption of Vibrio cholerae-contaminated food or drinking water. Vibrio cholerae bacteria work their way to your intestines where they produce important virulence compounds.

Virulence Factor #1: Cholera Toxin

Cholera toxin is an exotoxin protein that binds to human intestinal cells. The toxin interferes with the intestinal cells’ regulation of their water and salt balance. Cholera toxin exposure makes the intestines pour out gallons of water, giving you terrible diarrhea. People being treated for cholera in the hospital sleep on special cholera cots that have holes under their rear ends. If you’re curious you can check out a cholera cot here.Virulence Factor #2: Pilus

A second virulence factor is produced along with the toxin. It is a pilus—called the toxin co-regulated pilus, or TCP—that enables the cholera bacteria to stick to each other, as well as to human intestine. This enables the bacteria to both avoid host defenses and avoid being washed out by the deluge of liquid.Strains of Vibrio cholerae that can’t make the TCP pilus and/or cholera toxin are not pathogenic.

Over 3 million people a year are infected with Vibrio cholerae; most have mild symptoms, or not at all, but about one in ten require hospitalization. The biggest dangers of cholera lie in dehydration and salt loss due to diarrhea. Treatment is typically limited to rehydration and salt consumption. Nonetheless over 100,000 people die from cholera a year.

Cholera is spread through contaminated water, so it is rare in countries with clean drinking water supplies. Here’s a map of countries with cholera outbreaks in 2010 and 2011.

Syphilis

The disease syphilis is caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum. Unlike the bacteria that cause cholera, which live happily in sewers and rivers, Treponema pallidum cannot survive long outside of humans. These bacteria are spread by skin-to-skin contact between an uninfected person and a skin lesion, called a chancre, on an infected person.Treponema pallidum replicate rapidly at the site of infection, producing a lesion called a canker. They enter the bloodstream and then spread to other tissues. Syphilis becomes deadly when it reaches the brain.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease—named for Lyme, Connecticut—is spread by tick bites, but caused by the spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. The bacteria that cause Lyme disease prefer to live in deer, but can also live in humans where they cause flu-like symptoms. As Lyme disease develops further, it ultimately causes arthritis-like stiffness. The deer ticks that spread Lyme disease are called vectors, while deer are considered a reservoir for the bacterium. Just like most reservoirs hold extra water, deer serve as a constant stockpile of source of Lyme-disease-causing bacteria. Check out the ring pattern that follows a bite by Lyme-disease-carrying tick as well as a microscope image of Borrelia burgdorferi.

Legionnaires’ disease

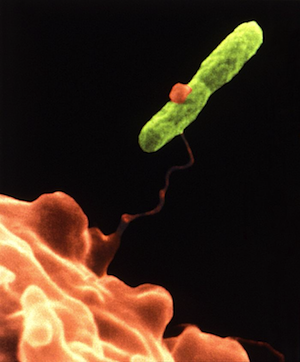

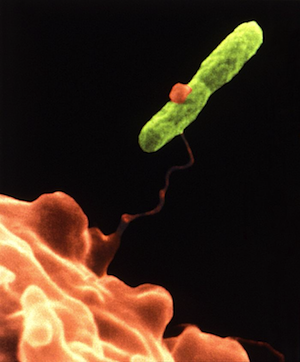

Legionnaires’ disease is a deadly disease that begins with cold-like symptoms. Just like Borrellia burgdorferi bacteria normally live in deer, the bacteria that cause Legionnaires' disease, Legionella pneumophila, typically inhabit single-celled amoeba cells. Here is an amoeba cell grabbing a Legionella cell. You might remember it from the opening of the chapter.

Legionella bacteria enter the body through inhalation of small droplets in liquid (called aerosols) into the lungs. The disease was unknown until it first struck at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976. Just like John Snow tracked cholera to a contaminated well in London, scientists tracked the first Legionnaires’ disease outbreak to contaminated water in the cooling system of the convention hotel.

Ulcers

It was long thought that ulcers happened from stress or consuming spicy foods. In the 1980’s, Australian microbiologist Barry Marshall turned this idea on its head. Biologists in the 19th century had noticed some spiral-shaped bacteria in the stomachs of patients with ulcers, but were unable to show a link between the bacteria and the disease.Marshall tried several different methods until he was able to culture enough of the bacteria, called Helicobacter pylori, to test if it caused ulcers. That’s right, he tested it Koch-style. Of course, it’s ethically challenging to hand human test subjects flasks of bacteria to see if they’ll give you an ulcer, so he tried it on himself. Think about that for a second. Would you catch yourself saying, "I’m going to drink this flask of bacteria…and if I’m lucky, just maybe I’ll get an ulcer at the end of it." Yeah, we probably wouldn’t say that either.

Marshall got his wish—and a Nobel Prize. Within a week, he began to develop stomach ulcers, and he saw an increase in the Helicobacter pylori in his stomach. Happily, antibiotic consumption killed off the bacteria in his stomach as well as those of other patients with ulcers. These other patients got the ulcers by the old fashioned way, which is still unknown. Stress and poor health habits are general risk factors for disease susceptibility. This may be especially true in the case of ulcers, where many people believed that ulcers were only caused by stress, with no infectious disease component.

Modes of Transmission

So in this section, we talked about a few different kinds of bacterial infections, all of them are transmitted through different means. To review:• Cholera is typically spread by eating or drinking contaminated food or water

• Syphilis is spread by direct skin contact between hosts

• Lyme disease is spread by insect vectors (deer ticks)

• Legionnaires’ disease is spread by inhaling aerosols

Scientists are still investigating how Helicobacter pylori, which cause ulcers, are spread. Some scientists believe it is through saliva, while others believe it may be spread by flies.

Understanding the cause of disease affects how they are treated. Rather than focusing on antibiotics, regions with high rates of cholera should probably focus on their water supply, while communities with incidence of Lyme disease might want to look towards controlling the deer or tick population.