Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

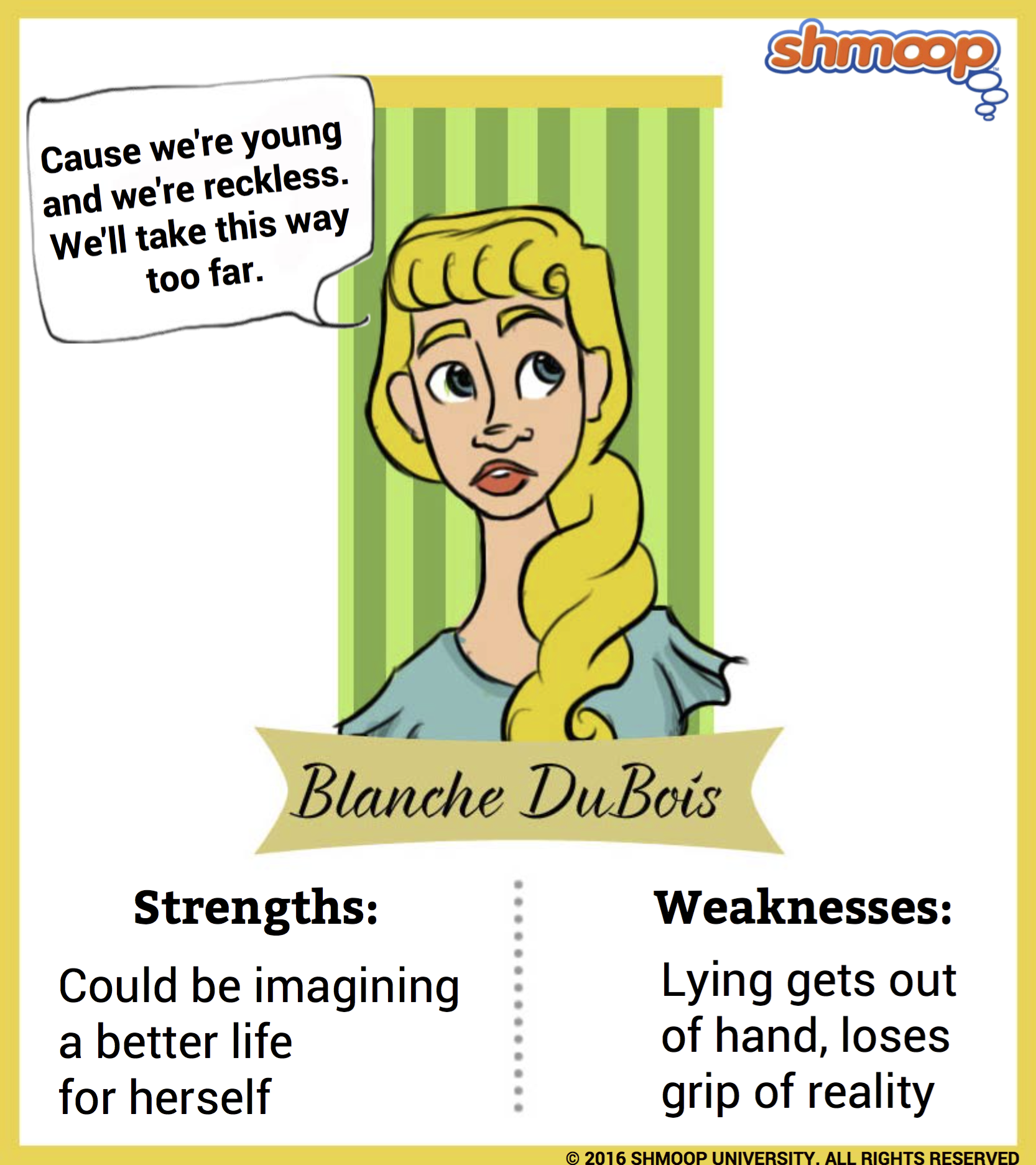

Blanche DuBois is an uber-tragic figure. She’s out of place both geographically and temporally (that is, she's stuck in the wrong time). Blanche is lost, confused, conflicted, lashing out in sexual ways, and living in her own fantasies.

Blanche and Her Retreat From Reality

Discussing Blanche's retreat from reality is interesting because it’s difficult to distinguish between when she has lost her grip on reality, when she’s simply imagining a better future for herself, and when she’s immersed in fiction and indulging in romantic fantasies. What start off as harmless flights of fancy soon escalate to a dangerous level.

At the beginning of the play, Blanche tells lies and knows that she's lying. For example, she tells her sister in Scene One that she’s simply taking a “leave of absence” from her job as a schoolteacher. We suspect at this point that she’s not telling the truth, and our suspicions are later confirmed. Does this mean that Blanche is deluding herself? No—it just means she’d rather not drop this bombshell on her sister immediately. This is a case of keeping up appearances.

But, later, when Blanche orchestrates a telegram to the supposedly rich and adoring Shep Huntleigh, it looks as though her fantasies are going overboard. Now she seems to believe them herself. When Tennessee Williams shows us what’s going on in Blanche’s head—the shadows on the wall, the voices echoing madly, the sound of the polka music (see “Symbols, Imagery, Allegory”), it’s his way of letting us know that, yes, we are correct in thinking that something is amiss. (Here’s an interesting question for you—is the Mexican woman selling flowers real, or is Blanche imagining her?)

But what drives Blanche over the edge? One explanation is that she spent so long lying to everyone else that she eventually believed her own lies. Remember when she tells Mitch, “Never inside, I didn’t lie in my heart” (9.59)? What she means is that she believed her own lies about her age and lady-like demeanor as much as he did. Of course, we can also look to Blanche’s husband’s death—and the death of all her relatives at Belle Reve—as another cause of her mental illness. After all, she is most haunted by that scene of Allan’s death, brought to us by the polka-music-and-gunshot memory.

We also have to remember that Blanche is an English teacher, and romance and fantasy are part of her profession. She famously tells Mitch:

“I don’t want realism, I want magic! [..] Yes, yes, magic! I try to give that to people. I misrepresent things to them. I don’t tell the truth, I tell what ought to be truth. And if that is sinful, then let me be damned for it!” (9.43)

Then, there’s the tipping point to Blanche’s wavering between sanity and madness—the rape. Stella foreshadows this when she tells her husband,

“You didn’t know Blanche as a girl. Nobody, nobody was tender and trusting as she was. But people like you abused her, and forced her to change.” (8.50)

It is indeed Stanley’s abuse that forces Blanche to continue her path of change—to retreat further from the reality that so clearly destroys her.

Whichever nuanced reasoning makes the most sense to you, we can likely agree that Blanche simply can’t deal with certain events and circumstances of her life. And, rather than face them, she chooses to retreat into a fantasy world of her own making. Does Williams condemn her for this? Not exactly. Blanche has had a pretty rough life, so you can't help but sympathize with her. And retreating is her coping mechanism.

Blanche the Elitist

Though we do feel sorry for Blanche, we can't ignore the fact that she’s a bit of a snob. Blanche has no money or prospects, and is essentially living off Stanley while she stays as a guest in his rather small and cramped apartment. Yet, as Stanley puts it, she acts like the Queen of the Nile.

She makes Stella run around buying her cokes because she “love[s] to be waited on.” She expects compliments from Stanley left and right regarding her looks. She soaks for hours in the bathtub when others are waiting to use it. And she flaunts herself shamelessly in front of a group of unsophisticated men who certainly don’t intend to pull out chairs for her and tip their hats in her direction. Worst of all is her treatment of Stanley as something sub-human or primitive because of his social standing. Her use of the derogatory slang “Polack” irritates the audience in addition to Stanley Kowalski.

Yet this, too, actually does garner a bit of sympathy for our protagonist. Blanche is living in a world that doesn’t really exist anymore, and we can’t help but feel sorry that her ideals are hopelessly out of date. In fact, it’s ironic that she urges her sister to move forward and progress with the world (rather than “hang back with the brutes”) when it is Blanche who is unable to move into modernity. Her vision of a man like Shep Huntleigh—the quintessential Southern gentleman—is as far from possibility as Stanley standing up to show respect when Blanche enters the room. What’s so interesting is that Blanche’s ideals about herself—as the quintessential Southern belle—are also completely false, but she can’t even recognize that her own actions clash with her self-image.

Blanche, Desire, and Tragedy

We talk a lot about the relationship between desire and destruction in "What’s Up With The Title?"—but what does it all mean to Blanche? Specifically, Blanche uses sex to seek refuge from destruction, totally unaware that she’s simply causing more death and disaster in the process.

It’s likely that she pursues inappropriately young men for two reasons: 1) to recapture the love she had with Allan when they were both young, and 2) because having sex with younger men makes her feel younger. It’s a way to recapture her youth (and we all know how touchy Blanche is about her age). What’s sad is that Blanche recognizes the folly of her ancestors, whose “epic fornications” brought them to ruin, yet doesn’t seem to realize that her own actions are doing the same.

This tragic irony is at the heart of her character, as shown by that famous last line of hers: “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers” (11.123). Strangers… strangers… have we heard this word before?

Yup. Sure have. Back in Scene Nine when Blanche finally admits to Mitch what she did back in Laurel:

"Yes,” she says, “I had many intimacies with strangers. After the death of Allan—intimacies with strangers was all I seemed able to fill my empty heart with." (9.55)

Blanche turns to strangers for comfort, but the only way she knows how to interact with them is through sex. These strangers weren't offering her kindness, as she deludes herself into thinking at the end of the play. It was simply “brute desire”—the same emotion that she accuses her sister of being consumed by.

Blanche and Stanley

The conflict between Blanche and Stanley drives a whole bunch of A Streetcar Named Desire. The 1951 film does an impressive job of driving home what might be difficult to see in the text alone—the epic sexual tension between Blanche and Stanley from the moment they first meet. Notice that Stella is out of the picture (in the bathroom washing her face) the first time Blanche encounters Stanley. They’re alone together. He takes off his shirt on the grounds that he wants to be “comfortable.” While Blanche pretends to be okay with this, we know later that such informalities in fact make her uncomfortable.

Later, there’s the constant proximity of Blanche to Stanley and Stella’s bed, which is more tension for all. When Stanley rifles through the personal things in Blanche’s trunk, it’s as though he’s violating her as well. The big “Stelll-ahhhhh!” scene is as much about Blanche’s discomfort with Stanley’s aggressive sexuality as it is fear for her sister. She’s horrified that Stella goes back downstairs in order to get in on with Stanley.

One important characteristic of Blanche is that she seems unable to relate to men in a non-sexual way, even men with whom it would be completely inappropriate for her to have a sexual relationship (like her brother-in-law, Stanley). In fact, she seems desperate to seek Stanley's sexual approval, and she’s always fishing for compliments about her physical appearance. After their first argument in Scene Two, she tells Stella:

"I called him a little boy and laughed and flirted. Yes, I was flirting with your husband!" (2.155)

Um. That's inappropriate.

What really tipped us off was this line in Scene Four:

"What such a man has to offer is animal force […]. But the only way to live with such a man is to – go to bed with him! And that’s your job – not mine!" (4.90)

Is Blanche jealous? We certainly know that she envies Stella the security and safe haven of her marriage while she, Blanche, was dealing with the loss of Belle Reve: “Where were you! In bed with your—Polack!” (1.185).

It’s interesting that Blanche chooses the word “bed” here, rather than simply berating Stella for her absence. It’s very possible that she resents the sexual freedom Stella enjoys as a married woman. By “freedom” we mean she can have sex any time she wants without reproach, albeit it with the same man. Blanche, by old Southern standards, shouldn’t be having sex at all... since she isn't married.

One of the most tragic aspects of this story is that we have a hard time imagining an alternative ending. During the rape scene when Stanley tells Blanche that they’ve “had this date with each other from the beginning,” we understand why he says it (10.81). Since Blanche is a woman who relates to men only on sexual levels, and Stanley is a man who relates to women only in a sexual manner, how can this play end happily? The heavy-duty sexual tension between these two is clear from the start, though whether Blanche is a conscious participant is up for debate.