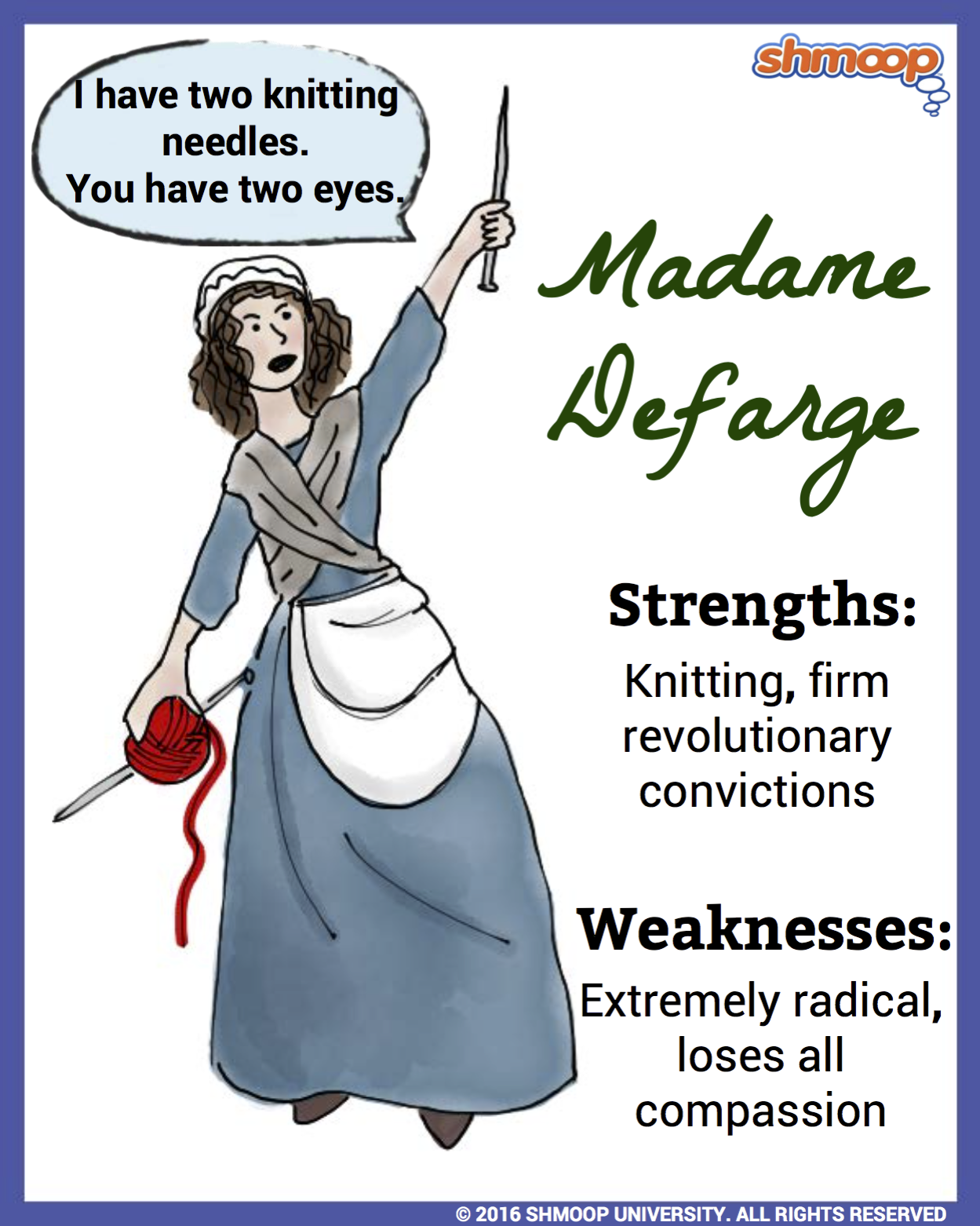

Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

You Mess With the Defarge, You Get the Horns

Madame Defarge is one piece of work. If anyone has a right to be upset about the abuses that the aristocracy heaps upon the commoners, she’s the person. After all, her sister was raped by the Marquis St. Evrémonde. Her father died of grief. Her brother was killed trying to avenge his sister's honor. All in all, she didn’t have the happiest of childhoods. It’s completely understandable that she’d want to play a big part in the revolutionary attempts to overthrow the power of the aristocracy.

Of course, we don’t know any of Madame Defarge’s back-story until the very last twists and turns of the novel. By this time, we’re pretty accustomed to a description of her as the implacable wife of Ernest Defarge, the woman who never stops knitting. She runs a wine shop in Saint Antoine that just happens to be the hub of all revolutionary activity. The lifeline of the revolutionaries, Madame Defarge knits a pattern that becomes a record of all the people whom the revolution will destroy. It’s a rather dire task, but someone has to do it.

By the time we learn Madame Defarge’s history, then, we’ve already heard over and over again how "cold," "dreadful," and "frightfully grand" she has become. She may be smart, but she’s also ruthless. We’re not ever really given a chance to sympathize with her or to mourn the horrors of her past. When Dickens gets around to telling us about them, Madame Defarge has already turned into something of a monster. The meeting between Lucie and Madame Defarge makes this absolutely clear: Lucie falls on her knees, begging for mercy on behalf of her child. Madame Defarge stares at her coldly. She doesn’t even stop knitting.

Cold As Ice

Her problem, it seems, is that Madame Defarge just doesn’t know where to draw the line. As far as she’s concerned, "justice" for the fate of her family isn’t just that the Marquis gets murdered. Justice should, she thinks, include the "extermination" of all of the Marquis’s family. Given her druthers, Charles, Lucie, and even little Lucie would fall under the sharp blade of La Guillotine. As Madame Defarge exclaims to her husband, "Tell the Wind and the Fire where to stop; not me!" (3.12.36).

With these words, Madame Defarge ceases to be human. All the other characters recognize her as a sheer force of nature. It’s logical, then, that readers would feel the same way: she evolves into a sort of meeting point of history and social opportunity. As our narrator writes, she is:

[...] imbued from her childhood with a brooding sense of wrong, and an inveterate hatred of a class, opportunity had developed her into a tigress. She was absolutely without pity. If she had ever had the virtue in her, it had quite gone out of her.

It was nothing to her, that an innocent man was to die for the sins of his forefathers; she saw, not him, but them. It was nothing to her, that his wife was to be made a widow and his daughter an orphan; that was insufficient punishment, because they were her natural enemies and her prey, and as such had no right to live. To appeal to her, was made hopeless by her having no sense of pity, even for herself. (3.14.33)

It’s fitting, in a way, that Madame Defarge should get killed by Miss Pross, Lucie’s guardian. Like Madame Defarge, Miss Pross has no real sense of her own self-worth. She lives entirely for Lucie. At the end of the day, only another totally relentless woman can undo Madame Defarge. Neatly, of course, Lucie manages to escape without ever getting her hands dirty.

If Madame Defarge doesn’t manage to win readers’ sympathy, she does raise some disturbing questions about the role of women in Dickens’s work. Why is it that women who want to become politically active seem to give over every ounce of their compassion and humanity? Why does Defarge get to remain a generally good guy while his wife descends into the realm of vicious monsters? Something about this seems generally unfair.

Well, yes. But then again, Victorian England wasn’t known for its attempts to establish gender equality. Lucie, with her golden curls, perfect home, and utter innocence, is a "good woman." Setting such standards doesn’t give Madame Defarge, the woman intent on finding political justice, much room to work with. It’s a bit hard to start a revolution and find lots of pretty knickknacks for the living room at the same time. We’re not trying to beat up on Lucie (you can read her "Character Analysis" for a discussion of her particular strengths); we’re just saying that Dickens seems to be pretty ambivalent about the role of women in revolution—or in public life at all.