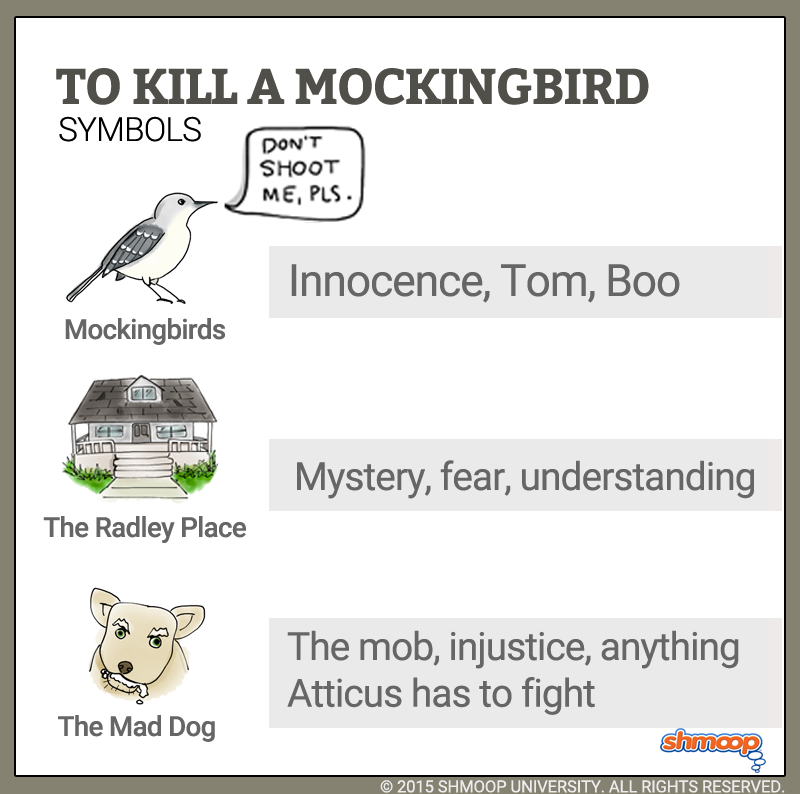

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

The title of the book is To Kill a Mockingbird, so we're thinking that mockingbirds must be important. They first appear when Jem and Scout are learning how to use their shiny new air rifles. Atticus won't teach them how to shoot, but he does give them one rule to follow.

"I'd rather you shot at tin cans in the back yard, but I know you'll go after birds. Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit 'em, but remember it's a sin to kill a mockingbird."

That was the only time I ever heard Atticus say it was a sin to do something, and I asked Miss Maudie about it.

"Your father's right," she said. "Mockingbirds don't do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don't eat up people's gardens, don't nest in corncribs, they don't do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That's why it's a sin to kill a mockingbird." (10.7)

So, mockingbirds are harmless, innocent creatures, and killing them is wrong, because they don't hurt anyone. (The same could be said for cows, but hamburgers are so tasty, while mockingbirds presumably aren't.) But is this lesson so important in itself that it's worth putting it front and center on the cover of the book?

Black and White and Red All Over

Mr. Underwood's editorial after the death of Tom Robinson doesn't mention mockingbirds by name, but it does have a similar message.

Mr. Underwood didn't talk about miscarriages of justice, he was writing so children could understand. Mr. Underwood simply figured it was a sin to kill cripples, be they standing, sitting, or escaping. He likened Tom's death to the senseless slaughter of songbirds by hunters and children, and Maycomb thought he was trying to write an editorial poetical enough to be reprinted in The Montgomery Advertiser. (25.27)

Mr. Underwood may be trying to get through to even the stupidest residents of Maycomb, but his editorial also makes sure that every reader gets the connection: the mockingbird and Tom are in the same class of beings. But why? Mr. Underwood says it's because of Tom's disability, though it's unclear why he thinks that makes a difference. Maybe it's along the lines of "women and children first": those thought to be weak should receive special protection.

Or maybe Tom's innocence of the crime he's accused of makes him similar to the mockingbird who does no harm to anyone. Or maybe it's the senselessness that's really key: killing Tom brought about no good and prevented no evil, just like shooting a mockingbird.

MockingBoo

Mockingbirds turn up once more in the book, when Scout is telling Atticus she understands about not dragging Boo into court.

Atticus looked like he needed cheering up. I ran to him and hugged him and kissed him with all my might. "Yes sir, I understand," I reassured him. "Mr. Tate was right."

Atticus disengaged himself and looked at me. "What do you mean?"

"Well, it'd be sort of like shootin' a mockingbird, wouldn't it?" (30.66-68)

All Boo does is watch the neighborhood, leave trinkets for Jem and Scout, and protect them when they're attacked. Like killing a mockingbird, arresting Boo would serve no useful purpose, and harm someone who never meant anyone any harm. So over the course of the novel, killing mockingbirds is associated with the sinful, the pointless, and the cruel.

On the one hand, linking particular characters to mockingbirds reduces them to the level of animals. On the other, it says that even animals are worthy of sympathy and the respect of being left alone if they're doing the same to you. By equating killing mockingbirds with wanton destruction, the book prompts us to take a step back from knee-jerk reactions (escaped convicts must be shot! murderers must be arrested!) and ask, what benefit is there? Why do this? What does it accomplish?

No mockingbirds were harmed in the making of this module.