Now that we're nice and comfy cozy with finding the values of trig functions, it is time to switch things up, literally. So far, we have learned how to find the value of the trig function given the angle. For instance, when we have the function y = sin x, we can find y whenever we know x.

We'll be going in the other direction now. We know y, the value of the function, but we don't know x, the angle that gets us that result. That's where the inverse trig functions come in:

If sin x = y, then sin-1 y = x.

We write the inverse of sine as sin-1. Some people get confused about the "-1" looking like an exponent (it's not), so sometimes we see the inverse written as arcsin instead. They are totes the same, though.

Of course cosine, tangent, and their reciprocals can all get in on this game as well, wearing little "-1" crowns or giving themselves "arc" as a fancy title. Just like the kings and queens they are pretending to be, each inverse function has a particular domain that they rule over.

Domain-ion

Not every function can have an inverse. It's an exclusive club, and the rules are all written down here. The big one is the horizontal line test—if a horizontal line can cross the original function multiple times, then it can't have an inverse.

Uh, sine, cosine, and tangent all fail that test. Miserably. Like, they somehow got negative points on the test. That's because they are periodic functions, so they're going to repeat their y values over and over again.

Obviously there's a way around this problem, or else we would be talking about something else entirely here. Like, maybe Battlestar Galactica, or The Parent Trap. What we do to get over this issue is to restrict the domain to just an area where it won't fail the horizontal line test.

Restricting sine's domain (somehow) improves its test scores, so now it can have an inverse, arcsine. Notice that the domain and range of sine get swapped over in arcsine. That is, sine could have y values between -1 and 1, and that is now the domain of arcsine. We've restricted the domain of sine to between  and

and  , and that's arcsine's range. And this means that sine, and arcsine, don't repeat themselves.

, and that's arcsine's range. And this means that sine, and arcsine, don't repeat themselves.

Here are the domains, and their associated ranges, for each inverse trig function.

| Function | Domain | Range |

| arcsin x | [-1,1] |  |

| arccos x | [-1,1] | [0, π] |

| arctan x | ( -∞, ∞) |  |

| arccsc x | (-∞, -1] and [1, ∞) |  and and  |

| arcsec x | (-∞, -1] and [1, ∞) |  and and |

| arccot x | (-∞, ∞) | [0, π] |

Don't go memorizing this table. We know, we've made you memorize a lot of stuff about trig functions already, but this is a bit too much. The only parts we'll work with on a regular basis are the ranges of arcsin, arccos, and arctan. And, like we mentioned before, they are related to the original trig functions' domains and ranges. So it is usually easier to reason out what our answer should be.

Plus, if we use a calculator on the inverse functions, it will automagically refuse stuff outside of the proper domain, and they give their results in the correct range. Forget friendship, calculators are all the magic we need.

Sample Problem

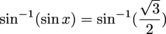

Solve  .

.

Let's keep our eyes on the prize here. We're looking for an angle x that, if we took the sine of that angle, would give us  . Sine and arcsine are inverses of each other, so if we apply arcsine to both sides of the equation, the sine will go away.

. Sine and arcsine are inverses of each other, so if we apply arcsine to both sides of the equation, the sine will go away.

Now we can try to solve for x. Taking another look at this, that  should look familiar to us. Think special triangles. Much like your little sister, you just can't get away from them. That's a good thing here though, because they make things easier on us. We don't even need a calculator for this one; all those who forgot their calculator, rejoice.

should look familiar to us. Think special triangles. Much like your little sister, you just can't get away from them. That's a good thing here though, because they make things easier on us. We don't even need a calculator for this one; all those who forgot their calculator, rejoice.

The special triangle that has a  in it is the 30-60-90 triangle. It's opposite the 60° angle, and the hypotenuse is 2. Sine is opposite side over hypotenuse, so that gets us exactly what we want.

in it is the 30-60-90 triangle. It's opposite the 60° angle, and the hypotenuse is 2. Sine is opposite side over hypotenuse, so that gets us exactly what we want.

Well, almost exactly. We work in radians nowadays, so we convert from 60° to  .

.

Sample Problem

Find  .

.

A lot of the time, the inverses for cosecant, secant, and cotangent make themselves scarce. They don't even show up on most calculators. We don't really mind, though, because we have our hands full dealing with arcsine, arccos, and arctangent.

Luckily, we can still MacGyver our way into finding those inverses. It can be a little tricky, though. Let's start off by rewriting the problem.

If we take the secant of the angle x, we get  . Secant is the inverse of cosine, though, which is much friendlier to work with.

. Secant is the inverse of cosine, though, which is much friendlier to work with.

We can rearrange this to get x back by itself again.

We started with  , and we changed it into

, and we changed it into  . So to go from an inverse function to its reciprocal, we have to take the reciprocal of the value instead. Trippy. It only takes a bit of duct tape and some elbow grease.

. So to go from an inverse function to its reciprocal, we have to take the reciprocal of the value instead. Trippy. It only takes a bit of duct tape and some elbow grease.

At this point we should recognize that x must be  . No other angle could be so daring.

. No other angle could be so daring.

We're starting to get good at these inverse functions, but there is one more sticking point. Sometimes we have to pick our answers based on the range of the inverse function. Remember, there are an infinite number of possibilities, but we are restricted to one. We decide based on which Quadrant our angle is based in.

We're going to throw you for one more loop, because loops are fun. Since it is possible for trig functions to have a negative value, it would probably be a good idea to know how to handle this. We come back to ASTC for this one. We decide which quadrant our angle is in based on the value of the trig function. For example, inverse cosine has a range of 0 to π, which is Quadrants I and II. If we have a negative cosine, we know that it must be in quadrant II because cosine is positive in I and negative in II.

Sample Problem

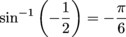

Find sin-1(-½).

Let's set the negative to the side for now. We will come back to that. Once again, we have a result that looks like it came from a special triangle, this time a 30-60-90 one. We picture it in our head, or maybe on our piece of paper, and try to find the (opposite over hypotenuse) that will get us ½.

If our triangle-drawing skills are to be believed, the 30° angle fits the bill. Our angle has an absolute value of 30°, or  . We're not done yet, though. Remember how we set the negative to the side earlier? Well, we're taking it back now.

. We're not done yet, though. Remember how we set the negative to the side earlier? Well, we're taking it back now.

Inverse sine has a range of  to

to  , which are in Quadrants I and IV. Sine is negative in quadrant IV, so our angle must be negative.

, which are in Quadrants I and IV. Sine is negative in quadrant IV, so our angle must be negative.

Always do a double check when working with negatives. Otherwise, we might leave things positive, and that would be a mistake this time.