Internet Research

Spoiler alert: Wikipedia is not a legit research site.

- Course Length: 1 week

- Course Type: Short Course

- Category:

- College Prep

- History and Social Science

- Life Skills

- Technology and Computer Science

- Middle School

- High School

Schools and Districts: We offer customized programs that won't break the bank. Get a quote.

If the idea of citing Wikipedia or Yahoo Answers doesn't make you cringe in horror, then this is the course for you. If "what did alexander the great do that was so great" sounds like a great search phrase, then this is the course for you. If "tiger AND physiology -Woods" is gibberish, then, yeah, this is the course for you.

This course is designed to give you all the tools you need to go from internet research newbie to total web guru and crush that "research" part of your research paper.

You'll learn to:

- use Google's extra fancy features to find exactly the information you're looking for

- evaluate the academic legitimacy of online sources

- cite internet sources without simply slapping down some URLs on paper

- organize your online research more meticulously than a squirrel stores his nuts

By the end of these four lessons, you'll be ready to take on that big, bad research paper with confidence.

Required Skills

This course assumes that students possess basic web know-how and an introductory understanding of what research is and is for. Beyond that, the course teaches all necessary skills.

Unit Breakdown

1 Internet Research - Internet Research for the Academic World

This course is the ultimate crash course to doing internet research for a school project or research paper. Topics include: How to find legit research sources on the internet, how to evaluate those sources, how to cite online stuff, and how to keep track of and organize online research.

Sample Lesson - Introduction

Lesson 1.01: Finding Sources Online

The year is 1990. The world's first search engine has just been born. It's a tiny program named Archie, which literally searched through the internet's files manually, because that's how tiny the internet was. To use it, you had to be in the computer lab of McGill University, familiar with computer code, and have pretty much nowhere else to be. A snuggie and a gallon of hot chocolate was also recommended.

So, how would you research a paper for school in 1990? Or self-diagnose yourself with ulcers and/or stomach cancer using WebMD? Or figure out how often elephants sleep?

It turns out you would have gone to an actual, physical library, used the Dewey Decimal System to find your topic or looked through the card catalog (which was basically like Indiana Jones decoding a treasure map, without the swagger factor), and then gathered up a bunch of books and sat down and read them, possibly using this ridiculous feature used in real books called an "index." It wasn't easy.

Today, of course, we've got things like Google, the Internet Archive, Project Gutenberg, a gazillion different academic search engines, and library databases. All these tools have definitely made research far more efficient, but it's a dangerous mistake to imagine that they make research easier. The internet is a vast sea of information, 80% of which is polluted, with 40-foot monster fish coming after you while a monster storm tries to dump you into the sea. It's larger than any single library has ever been, and finding the information you're looking for is a serious challenge. Anyone can post anything on the interwebs, and if you don't know what's legit or not, you might just believe the guy who's trying to convince you that the moonwalk was faked or that sugar will mutate your cells and turn you into an orangutan.

In this lesson, we're going to talk about the digital equivalent of the card catalog: search engines.

Sample Lesson - Reading

Reading 1.1.01: Google for Pros

Boolean Searching

Unless you've been stranded on a desert island for the last 15 years, or you're the kind of crazy old person that thinks the government is using laptop-microwaves to read your mind, then you're probably familiar with Google.

It's kind of a big deal.

But like we've been saying, making good Google searches is not as simple and easy as you might think. First, you've got to phrase your search in a way that's likely to get good results. So, imagine you're looking for information about women, specifically nurses, during World War II in France. Would you search a phrase, like "What did female nurses do in WWII France"? Would you just smash the keywords together and hope for the best, like "women nurses france WWII"?

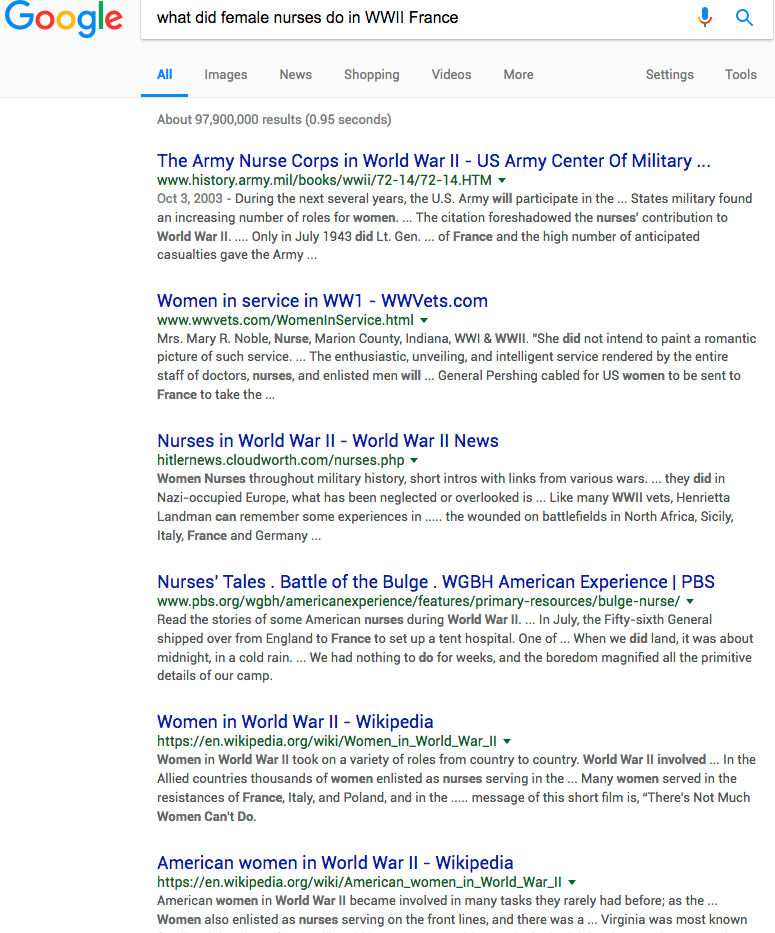

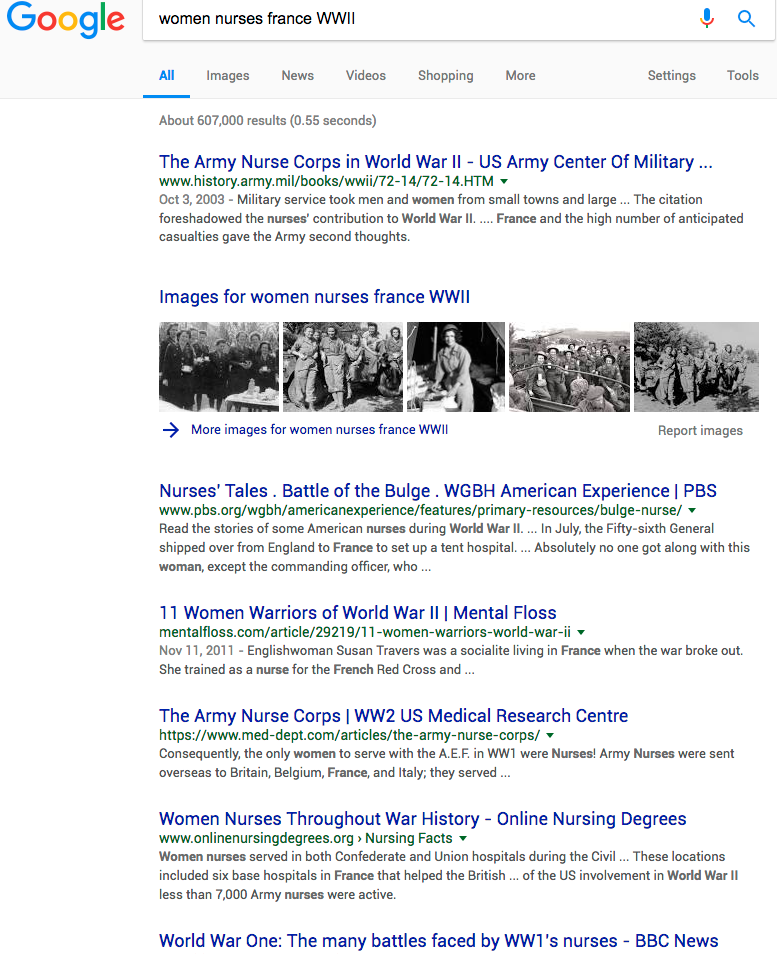

Here's what those two searches get you:

Search 1

Search 2

The first search gets us a top result from the Army's military history page and that's a reliable source. But then there's someone's blog compilation, a PBS page which is good, and some general stuff—ahem, Wikipedia—on women in war. It's a B- kind of search.

The second search starts with the same top result, another Army nurse corps result, the PBS page, and information on nurses throughout war history. Eh, we'd give that one a B+.

We can make these searches into A+ searches by figuring out how search engines work, and what kinds of operators they use.

Boolean Logic

The first thing we need to talk about is Boolean logic. That sounds like something from Doctor Who (Captain, the Booleans are attacking!), but it actually refers to the way we "talk" to search engines and give them instructions on how to use the search terms we type in. Note that Google has weird individual rules, so most of the information below applies to library searches or academic search engines.

Here are the rules and a few examples:

AND

When you stick AND in the middle of a search, it tells the search engine you want only results that have this word AND this word. In Google, a simple blank space is assumed to mean AND, but in other search engines it would look like this:

- women AND world war II AND nursing

OR

OR is a way to broaden your searches. It tells the search engine that you'll take results that have this word OR this word. Like so:

- nurses OR women

NOT

This is an especially useful one. It's a way of excluding certain terms from your results. So, if you were trying to look up Hawaiian history, but you kept getting touristy sites in your results, you would add NOT to the end of your search:

- hawaii history NOT tourism NOT travel NOT vacation

NEAR

This one's a little tricky. It tells the search engine that you want your two terms to be within ten words of each other. It can help if you've got two pretty different terms that you're trying to stick together, like atomic physics and Christianity. Goes like this:

- atomic AND physics NEAR christianity

Okay, let's pause. These are the basic concepts of Boolean searching, and it's pretty important to get the logic of them. Check out this site and play around with terms and phrases in the Boolean search box. Try to find information on the same topic using variations of terms and operators (you can see your search results below the box). Alright, more search tricks:

" "

Quotations are one of the more universal search rules. If you put several words in quotes, your search will only give you results with that specific phrase. That means you should only put logical phrases in quotes—you wouldn't expect an essay to have the line "women WWII nurses france" in it, so don't put quotes around it. Something like this would work better:

- "nurse corps" AND france AND WWII

*

All hail the asterisk. This is a little symbol that works like a wildcard within a word. If you use it right, it can save you from having to run multiple searches with slight differences, like this:

- nurs* would return results for nurse, nurses, nursing, and nursed, although it might also include words like nursery. militar* would return results for military, militaristic, and militarism.

?

The question mark works a lot like the asterisk, except there's only one letter that's wild. Like this:

- wom?n finds results for women and woman.

~

Last but not least, the tilde. It's our fave. That squiggly line indicates that you're searching for the specific term, or any of its close synonyms. Plus, it works in Google. Sometimes your searches are turning up what you need only because you're accidentally using an uncommon noun. Here's how to fix it:

- nurse AND WWII ~memoir would find you results with the words nurse and WWII in them, but also words like memoir, autobiography, account, record, chronicle, or narrative.

You know how we mentioned that Google has its own rules about search operators? Let's go over those. First, spend a second reading through Google's own list of operators.

Here's a few to pay particular attention to:

- site: This one is a lifesaver, especially when you're looking for legitimate, academic sources. You can type in your source like you normally would, and then type in site:.edu to limit the search to sites that end with ".edu" (those are websites from accredited academic institutions). You could also go with ".gov" or ".org" for government and nonprofit sites.

- - Google uses the "-" instead of NOT, but it works the same.

- * You can use the asterisk as a wild card for entire words in Google. Sweet.

Using Digital Searches to Get Physical Stuff

Up to this point we've been assuming that you want to use Google or other search engines to find online sources. Online sources are great, convenient, and plentiful. But once you actually dig in to your research, there's going to come a time when you need print sources. Yep, a book. That's not because print sources are just inherently, magically better than digital ones—it's just that not everything you need will be conveniently online for you.

We're talking libraries, folks. But, luckily, the days of card catalogs are long past. All your digital searching skills apply to library search engines. Generally speaking, all the Boolean operators we talked about will work in most library systems. If you're unsure, there's often a FAQ part of the website that mentions whether or not it's a Boolean system.

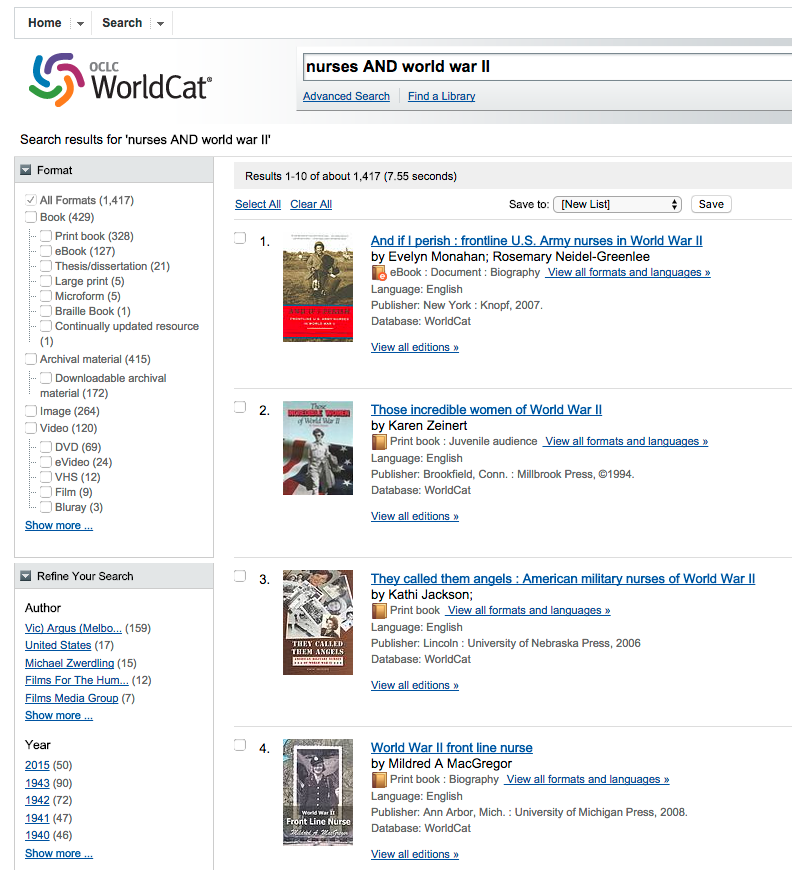

This is an example of a Boolean search in a public library system. Notice that there are only 30 results, but the first three (plus more) are exactly what we're looking for. You can think of libraries as curated collections of information, while the internet is an information free-for-all. It's like the difference between an art gallery and Etsy.

You're not limited, though, to the print sources that happen to be locally available in your high school or public library. Most libraries have a system called "Interlibrary Loan" or ILL, which lets you borrow a book from another public institution even if it's hundreds of miles away. How do you know what books other libraries have? WorldCat. WorldCat is a list of everything that's ever been published. Plus, it can tell you which libraries have copies of the book you're looking for.

If we plug the same search into WorldCat, we get over 1,000 results, all of which are published works. If you're interested in learning more about WorldCat, here are its own weird searching rules.

Sample Lesson - Activity

Activity 1.01: Screenshot Searching

Can't the internet just speak regular English? Before you forget everything you just read, let's do some internet searching. Practice makes good grades, right?

In this activity, we're going to give you four subjects to search, and let you compare and contrast the results. We'd prefer these searches to be in Google, but you should know that Google tailors its search results based on your browsing history, so it's best for the activity if you sign out of your Gmail account, if you have one.

Step One

First, open up Google in a new window and search these four subjects with the keywords you'd normally use (i.e., what you would have searched for before this lesson):

- The history of slavery in Bolivia

- The dietary habits of sea otters

- The development of Boolean math

- Cyber warfare and the Stuxnet virus

Step Two

Paste in screenshots of your first page of results in a Word document. If you don't know how to take screenshots, go here.

Step Three

Now do another search of each of those four subjects, but try to find higher quality and more specific results by using some of the operators and techniques we just talked about. We'd especially like to see more academic sources and more specific sources on your result list.

Step Four

Paste screenshots of those in the Word document, too. Be sure to label which screenshot is which.

Step Five

Finally, add a paragraph of five to seven sentences comparing and contrasting the results of each searching technique.

- Did you find that new operators were more helpful than straightforward key word searches? How so?

- Will this change the way you Google?

Representing Information w/ Visual Component Rubric - 30 Points

- Course Length: 1 week

- Course Type: Short Course

- Category:

- College Prep

- History and Social Science

- Life Skills

- Technology and Computer Science

- Middle School

- High School

Schools and Districts: We offer customized programs that won't break the bank. Get a quote.