The Research Paper

Because you don't need an M.A. to whip up a great research paper.

- Course Length: 2 weeks

- Course Type: Short Course

- Category:

- History and Social Science

- Writing

- Life Skills

- High School

Schools and Districts: We offer customized programs that won't break the bank. Get a quote.

At some point in life, a teacher or employer will tell you to go out into the world, gather information, and come up with your own ideas in the form of a research paper. Rather than run, hide in a closet, and bawl your eyes out in fear of coming up with your own ideas, Shmoop's a fan of proudly researching information, interpreting it, and forging your own brilliant thoughts.

This course is meant to elevate you to new heights of research glory. Writing a good research paper isn't something that just magically comes naturally to anybody—no kid learns their first letters and says, "Hmm, I think I'll analyze the use of dialogue in The Count of Monte Cristo." Instead, writing research papers is a skill that has to be learned, like everything else in school (or life).

We've broken this process down into easy, bite-size chunks. We'll be brainstorming for ideas, learning how to use the power of Google more effectively, and then crafting the most clearest thesis statements the world has ever seen. And that's only the beginning. Shmoop will hold your hands every step of the way, and in the end—you'll have a short, sweet, real-live-bona-fide research paper. More importantly, you'll have the ability to write a research paper without panicking, for the rest of your (long, glorious) career.

This course is designed to be a general introduction to the process of researching and writing a research paper, asking students to choose their own topics and take them from brainstorming to finished product. If you're a teacher assigning a specific research paper to a class, this course is a also a great and flexible companion for guiding students through that process, especially if it's their first time delving into the depths of research.

Required Skills

This is an introductory course which takes students from brainstorming to research to the finished paper. Basic writing, research, and organizational skills will be helpful, but are not required.

Unit Breakdown

1 The Research Paper - Writing a Research Paper

Specific topics covered include:

- Brainstorming and developing research questions

- How to research

- Evaluating sources

- Developing a thesis

- Organizing information

- Citations and plagiarism

- Outlining

- The writing process

- Editing and revising

Sample Lesson - Introduction

Lesson 1.01: Brainstorming and Research Questions

The first task in writing a good paper is to come up with a good idea—a stellar idea that will hold your interest for months, impress your teacher, and add to the sum of human knowledge. So, it's not like it's a big deal. Relax.

In this lesson, we're going to walk you through the tips, tricks, secrets, and mysteries of coming up with good research topics and questions. Because it definitely doesn't always work to sit yourself down and say, "Okay. Think of an awesome idea. Go. Now." Inspiration takes a little more work than that, usually. It takes some brainstorming. But if you think that brainstorming is just a silly way to waste time and doodle and write down a couple of keywords, then you've never met brainstorming Shmoop-style.

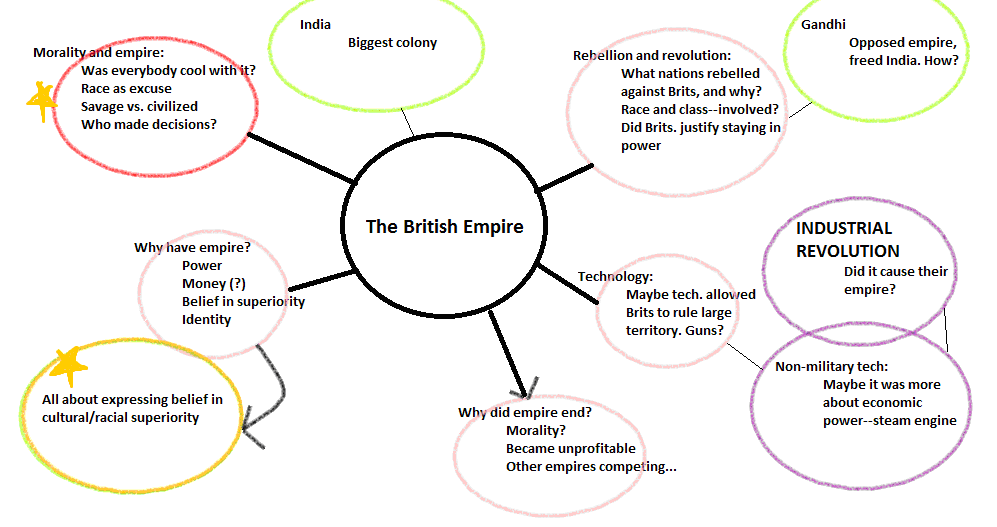

After you brainstorm, though, you've got to take some time to sift through your creative brain dump and develop some good, solid research questions. Mind maps like this one are pretty, but not so easy to turn into a paper. And also, we'd advise you to take the activity seriously here—the research questions you come up with are going to haunt you for the rest of this short course.

Sample Lesson - Reading

Reading 1.1.01: Making a Storm in Your Brain

When to Brainstorm

Technically, you could pick a brainstorming technique every time you needed to make a grocery list or pick a movie on Netflix, but the kinds of techniques we're going to talk about here are specifically for generating ideas for research projects. But first, a couple of important notes.

First, these brainstorming techniques are only going to help you if you're giving yourself time to use them. If you're trying to write a research paper in the 45 minutes before school…well, your research and writing is going to suffer. You could end up like one of these poor dudes.

Second, you won't always have free choice in your research topic. Well, obviously you can't write about the physics of sound waves for your American History paper. But different teachers will give you different levels of specificity on your prompt, from "American history" to "race relations in the 1900s" to "The Birth of a Nation and 1900s race relations." Most of these brainstorming techniques will work just dandy with a few strictures—we’ll be sure to note the adjustments you could make.

Brainstorming Techniques

Okay, but if you don’t have a prompt, where do you start? At the beginning.

The first thing you have to do is come up with some big, vague topics that you're personally interested in. If you don't personally care about colonial American laws, then don't study them. Your research subject has to be near and dear to your heart, or it'll be pure torture. Even if your teacher is making you choose a topic on a specific subject like World War II, you can still find a topic that interests you. Hate talking about guns and submarines and battles? Choose something sweet like propaganda posters.

Your big, vague ideas will probably just look like a bunch of keywords, like: the criminal justice system, the French Revolution, the ethics of video games, global warming, or maybe the migratory patterns of humpback whales. Don't worry about narrowing them yet; that's what the next steps are for. We're going to go over five different brainstorming techniques—and demonstrate them. You should be thinking about which methods suit you best.

Freewriting. Freewriting is just what it sounds like: you write freely about your subject. The idea is that you're just letting yourself write down your thoughts on a subject with no filters whatsoever (although drawing Smaug roasting hobbits over and over is probably not the best idea), and it will help you jog your creative smarts. It's a good idea to set a time for the exercise (for 10-15 minutes), and to tell yourself you must keep writing for the entire time. If we'd chosen "the British Empire," as our broad subject, this is what a freewrite might look like (although a real one would be longer):

The British Empire seems like way too big a subject. Wasn't it one of the biggest empires ever, including Rome? Which makes me wonder—how in the name of the Flying Spaghetti Monster did they keep control over an empire that big? Did people revolt? Probably. I would have. Oh wait, America did rebel. Wonder if other people did, and why. But that makes me wonder why the whole thing ended. If they were tough enough to keep control of half the known world for a few centuries, why did they suddenly fall apart?

Concept mapping. A concept map is a fun brainstorming technique, where you start with a blank piece of paper. You write your overall topic in the center of the page, and then start extending sub-topics out of it, and more subtopics out of those. It can be helpful to use lots of different colors to indicate linked ideas (who says work can't be pur-ty), or just to circle and star your favorite ideas. Just like in freewriting, it's important to keep going without time to stop and think about what you're writing. For "the British Empire," it might look something like this:

Three perspectives. Some people swear by this strategy, which is another writing exercise, but with a few more strictures. You take your big topic idea, and then you do three short exercises on it: describe it, trace it, and map it.

Describing your topic means talking about the who-what-where-when, and why it interests you and what makes it important. Tracing your topic means tracing its history and major influences. Mapping it means making connections between your topic and other similar topics. This system works best if you already know a thing or two about your topic, but you're looking for a great angle for your research. Like so:

- Describe it: The British Empire was the largest empire in human history, including almost 500 million people at its height. It was also the leading global power for more than a century. It interests me because I'm curious about the mechanics of controlling that many people—England is a tiny island, so how did it rule the world? I'm also curious about why it ended.

- Trace it: The Empire began as trading colonies in the 16th-18th centuries, which eventually evolved into settler societies. After several rebellions in the 18th century, the Empire changed directions and became more dominant in South Asia and East Africa. The Empire was financially profitable and successful, and an early example of globalization.

- Map it: The British Empire can be compared to other major empires, including the Spanish, Romans, and even American empires. Other disciplines are useful in studying it, including anthropologists, archaeologists, art historians, linguists, and political scientists. Very controversial part of history.

Similes. It is common knowledge that similes are the most fun-loving of literary devices, and so this strategy is a fun one—and a good one to combine with other strategies. It simply involves taking the sentence "__________ is/was like ______________" and filling in the blanks. You put your main topic (or maybe some sub topics) in the first blank, and just let yourself fill in the other blank with something. And you do it a bunch of times. Like this:

The British Empire was like a vast, tentacle octopus with a stranglehold on the world.

The British Empire was like a machine, where each colony was a part with a specific function.

The British Empire was like a nasty zombie-creature, which kept being killed by revolutions and then resurrecting itself and shambling onward.

The British Empire was like the book 1984, where everybody was brainwashed into thinking that holding power over a lot of people was a great, fun idea.

The economy of the British Empire was like the veins of the Empire, keeping it alive by pumping trade goods and money around the world.

The people in control of the British Empire were like parasites.

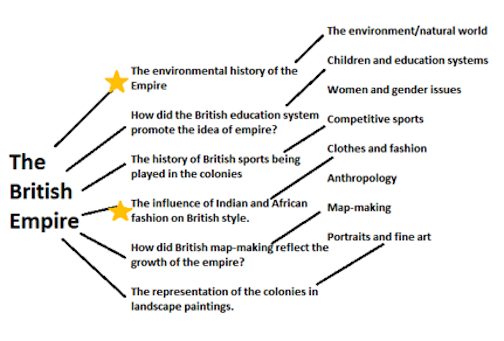

Making connections. If you're feeling like your topic is dull, or it's been done before, or you want to think outside the box (and avoid clichés like "think outside the box"), it can be helpful to make connections between two completely different topics that you love. So, we'd start with the British Empire, and list other big topics that we like, and try to find the common ground between them. It doesn't always work out, but it can lead to some really creative ideas:

Getting to the Questions

There's still a scary gap, you'll notice, between brainstorming a big pile of words, and getting to the point where you're ready to stand on a chair and declare a research topic with a fist pump (yelling "eureka!" is also fun). The process of picking a single subject can be challenging, especially if you collected some fist pump-worthy ideas during brainstorming. So as you look back over your brainstorming notes, you'll want to consider a few things:

- Look for ideas that are debatable. Try to find thoughts/concepts that don't feel like dead ends. So, "India was the biggest colony" is about 1000% less interesting than "Did the industrial revolution allow Britain to rule the world?"

- Look for the places you generated the most thoughts. If there's a dense part of your concept map, or a repeated idea in your freewrite, consider it more seriously.

- Look for nice, narrow topics. So, "revolution in the British Empire" is not as great as "Gandhi and the Indian Rebellion against the British Empire." You don't want to feel like your paper needs to be 60 pages to adequately cover your topic (and your teacher would rather watch The Bachelor than read that baby anyway).

Once you've got a nice narrow topic, you have to turn it into 2-3 good, solid questions. These are your research questions, which you'll be trying to answer in your paper. If we imagine that our narrow topic was "the environmental history of the British Empire," we might end up with questions like these:

- How did the British Empire affect the natural environment over time?

- Was the British Empire environmentally detrimental, or helpful?

- What were the major natural resources that the growth of the Empire consumed?

Sample Lesson - Activity

Activity 1.01: Now It's Your Turn

You might have seen this coming from 8.5 miles away, but now it's your turn to bust out some brainstorming techniques and develop some research questions. We don't want to put too much pressure on you, but these are the questions you'll be playing with for the whole course (spoiler alert: you'll have to write a paper!). So make sure you pick something you're genuinely interested in.

Here's the scoop:

Step One: Choose a broad topic you're interested in. It could be butterflies, skateboards, or video games, or anything else you think could turn up interesting research questions. If your teacher has already bestowed upon you a broad topic, then by all means use that. We don't want to step on anyone's toes much less ruin anyone's sparkly pedicure.

Step Two: Choose two of the five brainstorming techniques we went over in the reading section (freewrite, concept map, three perspectives, similes, making connections). Complete both brainstorming activities for your broad topic. They can be handwritten or made on the computer—just make sure you have a way to scan them in or take a picture of them if you choose the old pen and paper.

Step Three: Now, put on your night vision goggles (we hear those help) and review your brainstorming activities. Decide on a much narrower topic, just like we did for the British Empire. Maybe in your freewrite you wondered why more women don't skateboard professionally. Maybe in a concept map you have a bubble that says "women and skateboarding? Gender?" However it looks, find that narrow, interesting point.

Step Four: Finally, turn that narrower topic into 2-3 closely related research questions. We're not kidding about the closely-related part. We're talking fraternal twins close. You should be able to answer all 2-3 questions in a tightly-organized paper that doesn't feel like it was written by Sybil. So, women and skateboarding might become "Why is skateboarding a male-dominated sport? Is skateboarding culture actively exclusive, or just unappealing to women?"

Step Five: Include your narrow topic and research questions somewhere on your brainstorming notes, and turn all that stuff in!

Representing Information Rubric - 25 Points

- Course Length: 2 weeks

- Course Type: Short Course

- Category:

- History and Social Science

- Writing

- Life Skills

- High School

Schools and Districts: We offer customized programs that won't break the bank. Get a quote.