Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

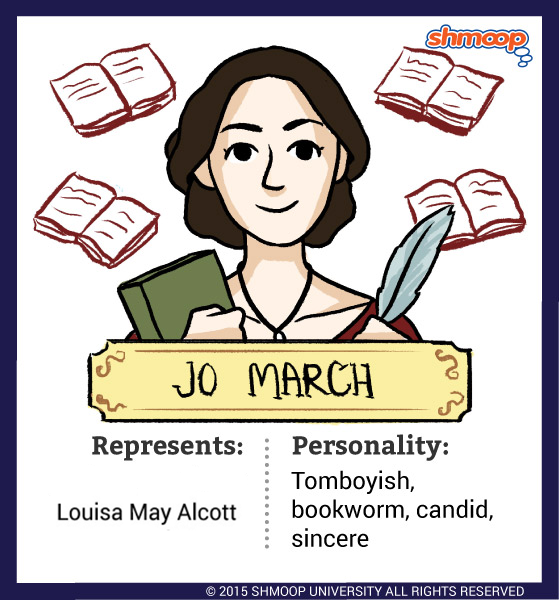

When we first meet Jo March, she's a tomboyish, hot-tempered, geeky fifteen-year-old girl. She loves activity and can't bear to be left on the sidelines; it drives her crazy that she can't go and fight in the Civil War alongside her father, who has volunteered as a chaplain. Instead, Jo has to stay at home and try to reconcile herself to a nineteenth-century woman's place in the domestic sphere, which is extremely difficult for her. You can hear the trouble in her name – she's called Josephine, a feminine name, but she goes by the more masculine-sounding Jo. She's clumsy, blunt, opinionated, and jolly. Her behavior is often most unladylike – she swears (mildly), burns her dress while warming herself at the fire, spills things on her only gloves, and barely tolerates her cranky old Aunt March. She's so boyish that Mr. March has referred to her as his "son JO" in the past, and her best friend Laurie sometimes calls her "my dear fellow."

Jo also loves literature, both reading and writing it. She composes plays for her sisters to perform and writes stories that she eventually gets published. She imitates Dickens and Shakespeare and Scott, and whenever she's not doing chores she curls up in her room, in a corner of the attic, or outside, completely absorbed in a good book.

Jo hopes to do something great when she grows up, although she's not sure what that might be – perhaps writing a great novel. Whatever it is, it's not going to involve getting married; Jo hates the idea of romance, because marriage might break up her family and separate her from the sisters she adores.

As you might have guessed, Jo is being set up for a Meaningful Journey of Self-Discovery and Surprises (TM). By the end of the novel, her dreams and dislikes are going to be turned topsy-turvy; her desire to make her way in the world and her distaste for staying at home will be altered forever. She may not find romance in the places that readers expect, but she will find it. She'll also realize that romantic love has its place, even though it changes the relationships you already have. As Jo discovers her feminine side, she also figures out how to balance her ambitious nature with the constraints placed on nineteenth-century women. The question is: how much do these constraints reflect the contemporary situation of twenty-first-century women readers?

Louisa Between the Lines

Jo begins as a semi-autobiographical stand-in for the author, Louisa May Alcott. Like Jo, Alcott was one of four sisters, with a philosophically-minded father, strong religious principles, and a penchant for writing. Alcott, however, never married, although she adopted her deceased sister's child and thus experienced something like motherhood. The first half of Little Women (Chapters 1-23) is pretty much a fictional version of Louisa May Alcott's own life with her sisters, including the same kinds of domestic trials and triumphs that they experienced every day. However, after readers clamored for Jo to marry her best friend, Laurie, Alcott realized that she couldn't get away with creating a beloved heroine and leaving her a spinster. Not in the nineteenth century, anyway. So Alcott invented a romance for Jo in the second half of the novel – just not the one that anyone expected!

Another important similarity between Alcott and Jo is the kind of stories they write. Louisa May Alcott herself wrote both realistic, moralized fiction, like Little Women and its sequels, and sensational thrillers. Of course, she published those under a pseudonym, but you can read some of her most exciting stuff in the anthology Alternative Alcott, which we highly recommend. Like Alcott, Jo begins her publishing career by writing thrilling stories with Gothic inspiration and no morals whatsoever – the written version of horror films and historical thrillers. And also like Alcott, Jo is most successful as a writer when she produces sentimental works about everyday domestic life. We guess it's just one more piece of evidence in favor of that constant advice to young writers to "write what you know."

As you read the novel, see if you can feel the difference between the places where Louisa is writing based on her own experience and the places where she's making things up.

Sisters Doing It for Themselves

The four March sisters are extremely close, but their relationships with one another are varied and complex. Jo is closest to her sister Beth, who is two years younger than her. With Jo and Beth, it's a case of opposites attracting; Jo is brash, overbearing, and ambitious, while Beth is a sweet, shy homebody. Jo describes Beth as her "conscience" at one point, and Beth does seem to rein in her wild sister sometimes. Beth's legacy to Jo is her role as a helpmeet and comfort for her parents and for the whole family in times of trouble. Jo seems to inherit Beth's role as the "angel in the house," and by watching and understanding Beth's role, Jo becomes more comfortable with her own femininity and with performing in the domestic sphere.

Jo's relationships with her other two sisters, Meg and Amy, are equally loving, but involve more conflict. As the two oldest sisters, Meg and Jo share a lot of experiences. They become young women and enter into society together. (By "society," we mostly mean "house parties hosted by their rich friends.") Because of their poverty, they're also called upon early in life to begin taking over some extra responsibilities – looking after their two younger sisters, keeping the household running, and even taking on outside jobs to help support their struggling family. These shared experiences create a special bond between Meg and Jo; in fact, when it seems like Meg might get married, Jo says that she wishes she could marry Meg herself to keep the family together. Yet Jo and Meg have very different value systems – Meg values pretty things and high society and has a romantic nature, and Jo scorns almost everything Meg thinks is important.

Jo and Amy are the most explosive pairing of the March sisters. Jo has very little patience with Amy's attempts to be snobbish and proper, and when Amy is really little Jo treats her a bit condescendingly. The first time we see them together, on Christmas Eve, they're only too ready to say that they hate each other. Amy and Jo both have fiery tempers, and there are a few times that we're worried they might hold grudges for life – such as the time that Amy burns Jo's only copy of a book manuscript. But their faith and their love for their family continually hold them together, despite all the things that might pull them apart.

Working Girl

For most of the novel, Jo has a job – something a bit unusual for a young lady with an upper-class background in nineteenth-century America. Even when we first meet Jo, aged fifteen, she works as a companion for her Aunt March. Being a "companion" to a rich old lady, or even a rich young lady, was a common form of employment for nineteenth-century girls who came from good families but didn't have much money of their own.

Like most companions, Jo spends time with her employer, reads to her, does little tasks for her like winding her yarn, and generally hangs around. This might not sound too hard, but Jo's Aunt March is a tyrannical, selfish old woman whose favorite phrase is "I told you so." She constantly rebukes Jo for her unladylike behavior, and Jo bristles under her watchful eye. Imagine if you, aged fifteen, had to spend each day with a crotchety relative instead of going to school. You thought P.E. was bad? Try Polly, Aunt March's spoiled parrot. But even though it's not a bed of roses, Jo's job as Aunt March's companion helps her contribute a little money to her struggling family.

Jo eventually loses her job as Aunt March's companion to Amy, but goes on to work as a governess to the children of a family friend, Mrs. Kirke, at a boarding house in New York. In this case, Jo's employment continues to help her take care of her family, especially her ailing sister Beth. But it also gives her a chance to see the world beyond the New England town where she grew up. While working this job, Jo lands another – as a contributor of sensational stories to a newspaper (well, it's more like a tabloid) called The Weekly Volcano. But this is the job that finally teaches her that some things aren't for sale – including her honesty and integrity. Jo feels herself becoming desensitized and corrupted by the gratuitous material in her stories, and she gives up the position.

When Jo returns home from New York, it seems like she might reconcile herself to staying at home, caring for her parents, and being the "angel in the house" that nineteenth-century culture suggested women should be. But she's got one more trick up her sleeve – her plan to open up a boarding school for boys. Jo's final career choice brings together her love of boys and her homemaking skills with her interest in education and literature. It's the perfect compromise between being a mother and being an educator. It's also Louisa May Alcott trying to have her cake and eat it too – Jo is a stay-at-home mom, but also an entrepreneur. It's a beautiful dream, but maybe not realistic for everyone.

Don't Splice that YouTube Fan Vid Yet

Probably the most controversial thing about Jo is the love triangle she ends up in. Well, to be exact, there are two love triangles. (At this point, if you haven't finished reading the novel, you should go back and do that because we're about to drop some mad spoilers.) First, of course, there's the Amy-Laurie-Jo triangle. For most of the novel, you probably thought Jo was going to end up with Laurie. After all, Laurie and Jo are best buds. Whenever Jo is in trouble, she runs to Laurie, and sometimes she even buries herself in his arms. They talk about running away together, and Jo is comforted when Laurie says he'll always be there for her. Plus, Jo's tomboyishness seems to dovetail perfectly with Laurie's effeminacy, right? It's a complete gender-swap! He even has a girlish name, while she has a boyish one.

If you thought Laurie + Jo was a match made in heaven, well, at one point Laurie would have agreed with you. Heck, there are plenty of people who read the novel today who would also agree with you. But Alcott refuses to let Jo and Laurie get together. Now, don't go all crazy on us, but we actually hear what she's saying on this one. Laurie and Jo actually aren't a good pairing, because they're both too hot-tempered. Plus, we don't think Jo could be happy as the wife of a rich man; she's not fashionable enough to be a queen of high society. We can just see them trying to hold their first house party – Jo would probably break all the best china, spill something on the most important guest, and swear in front of the next most important guest in the first five minutes.

We also like the fact that Jo turns Laurie down because she's true to herself. Sure, he's rich, and good-looking, and a good person, and in love with her, but she just doesn't feel the same about him. She likes him a lot, but she's not attracted to him. And, well, love isn't something you can force. Neither is, ahem, attraction. And sometimes "no" is nicer than "maybe." We think Jo puts it best: "I can't say 'yes' truly, so I won't say it at all." So Laurie heads off and ends up with...Jo's sister Amy. Yeah, that one's a little weird. We'll save our discussion of it for Laurie's "Character Analysis," so you can skip over and read that if you want.

And then begins the next triangle: Laurie-Jo-Mr. Bhaer. Again, don't freak out when we say this, but Mr. Bhaer is basically a completely ridiculous love interest for Jo. If you don't believe us, you can go and read Louisa May Alcott's journals, where she referred to Mr. Bhaer as " a funny match" for Jo. Mr. Bhaer is about fourteen years older than Jo (he's around 40 when she's 26), he's definitely not handsome, he has terrible table manners, his clothes are always ragged, and he's got a silly accent. It's not that we don't like German accents (we do!), but we think that Alcott makes Mr. Bhaer's accent sound extra-silly on purpose, to emphasize his buffoonishness. (Feel free to disagree with us – see Mr. Bhaer's "Character Analysis" for more!)

In the end, of course, Jo's decision to marry Mr. Bhaer instead of Laurie says more about her than it does about him, or even about Louisa May Alcott snickering as she messes around with her readers. Jo isn't the kind of person who marries for money or for appearances – she marries because she has a deep love and respect for someone, and because she thinks they'll be excellent partners in life. The first hint comes when Mr. Bhaer reminds Jo of her father during a discussion of theology. When Mr. Bhaer defends traditional religious values in the face of modern philosophy, Jo starts to lose her heart. No, it's not especially romantic, but that's the kind of girl she is.