We all need a shelter, a safe haven when things get rough. A place we can go when we need to get in touch with ourselves again. For some, it's a physical place like a room or a mountaintop. For others, it's more symbolic, like the open road or their hobbies.

Where better for 2D shapes to find themselves than on the x-y coordinate plane? There's plenty of legroom for as many shapes as we need, and plotted points will help these shapes find themselves. Literally.

If 2D shapes can live on the x-y plane, we can use the nature of the Cartesian coordinate system to help us find the areas of these figures. In other words, we'll need our trusty distance formula to help us find bases, heights, diagonals, and radii. However, unlike finding perimeters and side lengths, area is different because the formulas for area differ based on the shapes we have.

To be sure of which formula we need to use, it's best to actually draw everything out so we can be certain that the shapes are what we think they are (for instance, a rhombus and not a kite).

Sample Problem

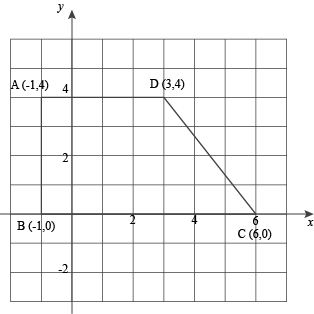

A quadrilateral has four vertices at A (-1, 4), B (-1, 0), C (6, 0), and D (3, 4). What is the area of the quadrilateral?

At first glance, it might be tough to tell exactly which formula to use. After all, do we have a rectangle? A kite? A parallelogram? Actually plotting the points might give us a better sense of which formula to use.

Much better. It's fairly obvious now that we have a right trapezoid. (If you don't believe that, make sure the slopes of AD and BC are equal and that AB has a slope that's the negative reciprocal.)

Now we know to use the formula A = ½(b1 + b2)h. The two parallel sides, AD and BC, are the bases and luckily, we know that AB is the height. Since the trapezoid is aligned to the grid, we don't even have to use the distance formula.

A = 22 units2

Unfortunately, not all shapes take such a comfortable position on the coordinate plane. Some require us to use the distance formula.

Sample Problem

A circle with center (-2, 2) has a radius that extends to (1, 0). What is the area of the circle?

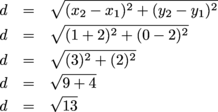

We know that the area of a circle is A = πr2, so that's an excellent start. We're given two points: one is the center and the other is a point on the circle. The radius must be the distance between these two points.

Our radius is  units long. The problem asks for area, so we can plug this into the area formula for a circle.

units long. The problem asks for area, so we can plug this into the area formula for a circle.

A = πr2

A = π( )2

)2

A = 13π ≈ 40.8 units2

So far, we've only looked at the areas of triangles and various quadrilaterals. We threw circles in there for good measure, but what about the billions of other polygons that we haven't talked about? Do they have individual area formulas too? Probably, but instead of memorizing them all, we can simplify our lives a great deal. All it takes is a little common sense in the form of a neat little postulate.

The Area Addition Postulate says that if we have two shapes that do not overlap, the total area equals the sum of the areas of the individual shapes. In other words, if we can cut up a shape into triangles, quadrilaterals or portions of circles, we can calculate the area of the shape by adding up the areas of the pieces. That leaves our brains with room to memorize other things like phone numbers and passwords and Monty Python's entire dead parrot sketch.

Sample Problem

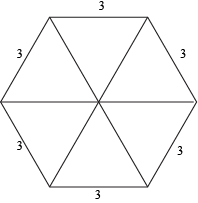

What is the area of this regular hexagon?

We can split a regular hexagon into six different equilateral triangles. If we calculate the area of each triangle and add them up, we'll have the area of the total hexagon.

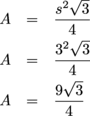

We already know the area formula for an equilateral triangle. Since each side is 3, all we have to do is plug in s = 3.

Since the hexagon is six of these triangles, we can multiply the area by six to find the total area.

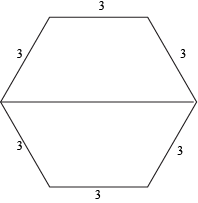

If we wanted, we could check this accuracy by splitting the hexagon into two isosceles trapezoids.

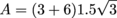

The area of a trapezoid is ½(b1 + b2)h, so the area of both these congruent trapezoids combined is just A = (b1 + b2)h. In this case, we know that b1 = 3 and b2 = 6. The height is a little trickier to calculate, but using 30-60-90 right triangles, we can find that it's  . That means the total area of the hexagon is:

. That means the total area of the hexagon is:

A = (b1 + b2)h

They're the same. The Area Addition Postulate holds up.